Slavery in North Dakota

North Dakota’s historical engagement with slavery occupies a subtle yet profoundly significant place in the broader narrative of American enslavement. The state, situated in the northern plains and often perceived as a peripheral territory, was not characterized by the plantation economies that dominated the South. Yet its connection to slavery and its enduring legacies cannot be overlooked.

The African American presence in North Dakota, while numerically limited, reflects a convergence of systemic forces, federal policy, and individual agency that is emblematic of the post-emancipation experience across northern and western territories. Examining North Dakota’s relationship with slavery requires an understanding of both direct and indirect connections—legal frameworks inherited from the Dakota Territory, migration patterns of freed African Americans, and the broader social and economic reverberations that slavery produced across the United States.

The historiography of slavery in North Dakota has historically been constrained by the perception of geographical marginality. Yet scholarship increasingly recognizes that African Americans played pivotal roles in shaping the territorial and early state society, and that their labor, resilience, and activism intersected with structures emerging from the nation’s slaveholding past.

In this context, the state serves as a prism through which to explore the indirect consequences of slavery: the movement of freed people into frontier territories, the establishment of African American homesteads and communities, and the persistent inequities in economic and social life derived from historical exclusion. This essay situates North Dakota within the broader American experience of slavery, emancipation, and reconstruction, offering a comprehensive examination of legal, social, and economic dimensions, as well as the lives of notable African Americans whose agency shaped the region’s development.

The African American presence in North Dakota predates statehood and emerges most prominently through the narratives of explorers, traders, and early settlers. York, the enslaved companion of Lewis and Clark, exemplifies this early engagement. His role in the expedition illustrates the paradox of African American labor: while legally enslaved, he exercised considerable skill, knowledge, and agency that were critical to the expedition’s success.

York’s interactions with Native American populations and his participation in surveying and documenting the land reveal both the visibility and invisibility of African Americans in frontier history. Despite being a figure of historical significance, York’s contributions were long marginalized in traditional historiography, reflecting a broader trend of erasure that characterizes African American participation in northern and western territories.

Beyond York, other African Americans migrated into the Dakota Territory in small numbers, often through their involvement in fur trade networks or as laborers on frontier settlements. The cultural and economic contributions of these early settlers set the stage for subsequent waves of migration after the abolition of slavery.

These individuals navigated complex interactions with indigenous populations, Euro-American settlers, and territorial authorities, reflecting the layered social hierarchies of a frontier society. Their presence illustrates how the reach of slavery extended beyond the geographic confines of the South: the institution’s legacies influenced migration patterns, labor practices, and social hierarchies even in territories where formal enslavement was legally proscribed.

Legal structures in the Dakota Territory played a pivotal role in shaping African American experiences and settlement opportunities. The 1862 territorial criminal code, which prohibited kidnapping, effectively outlawed slavery by codifying it as a criminal act. This legislative framework aligned the territory with Northern anti-slavery principles, distinguishing it from the Southern slaveholding states and providing a modicum of legal security for freed African Americans seeking to establish homesteads. However, enforcement of these laws was uneven due to the sparse population and limited administrative capacity, illustrating the tension between legal ideals and practical governance on the frontier.

The territorial legal environment also intersected with federal land policies, most notably the Homestead Act, which permitted settlers, including African Americans, to claim and cultivate property. These legal mechanisms were instrumental in facilitating African American migration to North Dakota and were essential in constructing pathways toward economic self-sufficiency and social autonomy.

However, legal protections existed within a broader context of structural constraints, including social exclusion, informal discriminatory practices, and the negotiation of territorial hierarchies that privileged European settlers. Thus, while the Dakota Territory’s legal framework was formally aligned with anti-slavery principles, African Americans’ ability to leverage these structures depended upon resourcefulness, community solidarity, and engagement with both local and federal institutions.

The post-Civil War period catalyzed a significant migration of freed African Americans into northern and western territories, with North Dakota emerging as a site of opportunity and relative safety. This movement was intimately tied to broader social dynamics, including the Exoduster movement, in which African Americans relocated from the South to escape systemic oppression, racial violence, and disenfranchisement. North Dakota’s open lands, made accessible through the Homestead Act, attracted freedmen seeking both economic security and the ability to establish self-determining communities.

African American settlers in North Dakota demonstrated remarkable adaptability. They applied agricultural knowledge acquired in the South to the unique climatic challenges of the northern plains, implementing crop rotation, soil management, and community labor strategies to sustain farms. Settlers often organized along familial, religious, and mutual aid networks, creating microcosms of African American civic life in a predominantly white territory. While the population was small, the concentration of freedmen in certain counties allowed for the development of cohesive communities capable of mutual support and collective action.

The migration experience, however, was fraught with challenges. Environmental hardship, social marginalization, and limited access to capital constrained the economic prospects of settlers. Discrimination in education, commerce, and political participation further complicated efforts to establish long-term stability. Yet these settlers’ perseverance not only ensured survival but also contributed to the demographic and economic diversification of the territory, establishing patterns of African American agency and settlement that would resonate for decades.

The economic integration of African Americans into North Dakota’s agrarian and commercial systems was both a testament to resilience and an illustration of structural inequities. Following the passage of the Homestead Act in 1862, African American settlers were afforded formal avenues to claim land and cultivate farms.

This legislative framework facilitated not only physical settlement but also the assertion of economic autonomy, a critical component of post-emancipation life. However, the realities of North Dakota’s frontier environment presented formidable challenges. The extreme seasonal variability, unpredictable precipitation, and often nutrient-poor soils necessitated innovative farming practices and adaptive strategies for survival. Settlers relied upon techniques such as crop rotation, intercropping, and shared labor networks to maximize productivity and mitigate environmental risks.

Beyond agriculture, African Americans established commercial enterprises that contributed to local economies and provided essential goods and services. Small businesses, including general stores, blacksmithing operations, and transport services, were often operated collectively or within tightly knit community networks, reflecting both economic necessity and cultural solidarity.

These enterprises were critical in fostering community cohesion and enhancing social capital within African American settlements. Furthermore, entrepreneurial success among African Americans challenged prevailing racial stereotypes, demonstrating that economic competence and civic engagement could thrive outside of the Southern slaveholding context.

Nonetheless, African Americans faced persistent systemic barriers. Access to credit and banking services was constrained by racial discrimination, and property disputes were often complicated by local legal practices that favored European settlers.

Social isolation and segregation further inhibited participation in broader commercial and civic life, compelling African American communities to develop self-reliant social institutions, including churches, schools, and mutual aid societies. Despite these structural obstacles, African Americans in North Dakota achieved notable economic milestones, laying the groundwork for subsequent generations and contributing materially and socially to the development of the state.

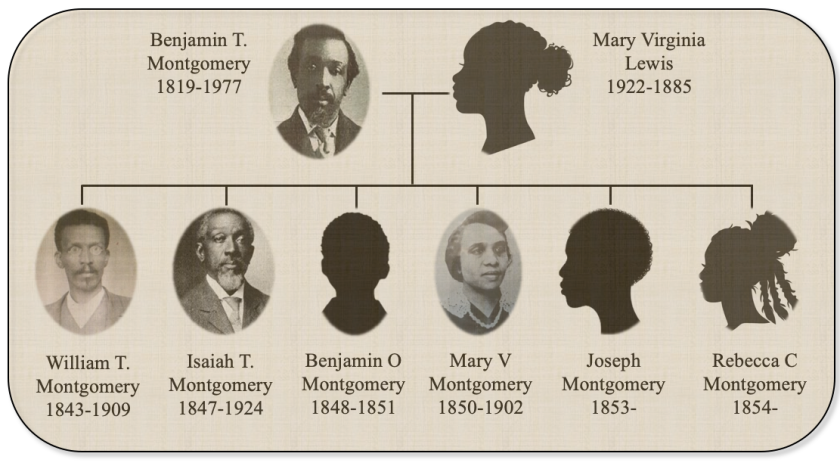

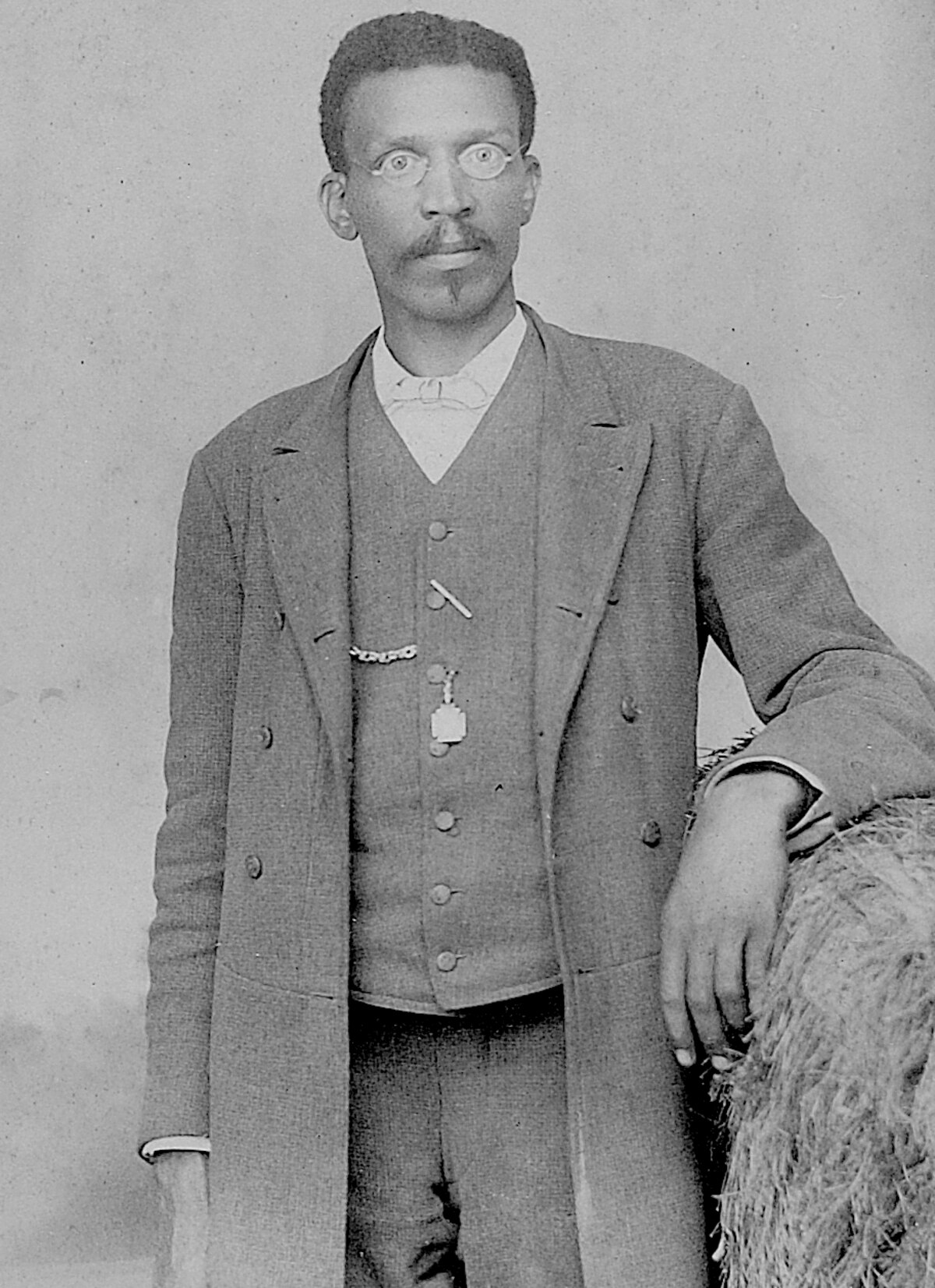

William Thornton Montgomery serves as an emblematic figure in North Dakota’s African American history, illustrating the intersection of personal agency, structural opportunity, and the enduring impact of slavery’s legacies. Born into slavery in Mississippi, Montgomery’s trajectory reflects both the constraints imposed by the institution and the possibilities created by emancipation. Migrating to North Dakota, he established a substantial homestead and developed a range of economic ventures that positioned him as one of the most prominent African American landowners in the state.

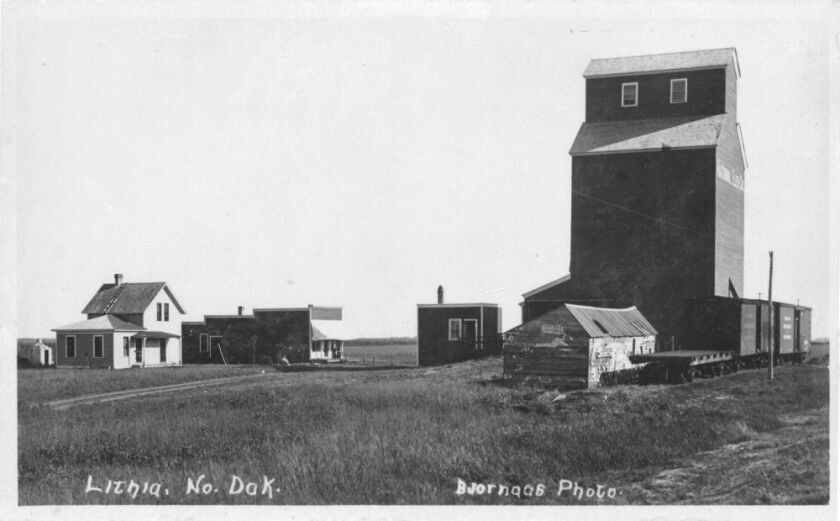

Montgomery’s founding of Lithia represents a unique instance of African American town establishment in North Dakota, reflecting both entrepreneurial vision and the desire for communal autonomy. The town functioned not only as an economic hub but also as a social and cultural anchor for African Americans in a predominantly white settler landscape. Montgomery leveraged both federal land policies and local networks to secure property and resources, negotiating racial hierarchies and asserting agency within a context that was often structurally limiting.

His legacy extends beyond economic achievement. Montgomery’s leadership cultivated a sense of identity, resilience, and cohesion among African American settlers, offering a model for community organization and civic participation. Lithia’s existence, though historically marginalized in mainstream accounts, provides tangible evidence of African American autonomy and contributes to a broader understanding of the diverse experiences of freedmen in North Dakota.

Montgomery’s life exemplifies how individual initiative intersected with structural opportunities, including federal land legislation and the relative openness of frontier settlement, to create spaces of African American self-determination. His story challenges the conventional historical narrative that situates African American success solely in urban centers or Southern states and underscores the importance of northern and western territories in post-emancipation African American history. Moreover, Montgomery’s example illustrates how African Americans negotiated economic and social agency in spaces historically dominated by Euro-American settlers, forging communities that reflected resilience, resourcefulness, and an enduring commitment to communal prosperity.

The Freedmen’s Bureau, officially the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, played a critical, though understated, role in North Dakota’s African American history. Established in 1865, its mission extended beyond immediate relief to encompass education, legal advocacy, and land allocation. While the bulk of its operations occurred in the Southern states, the Bureau’s mandate reached northern and western territories, providing a framework through which African Americans could assert economic, legal, and social agency. In North Dakota, the Bureau’s work was primarily concentrated on assisting freedmen with homestead claims, literacy programs, and access to social services—interventions crucial for enabling African Americans to transition from enslavement to civic participation.

Education was a central focus of the Bureau’s initiatives. Freedmen and their descendants often arrived in North Dakota with limited formal schooling, reflecting the systemic educational deprivation of slavery. The Bureau facilitated the establishment of schools, providing teachers, supplies, and curricula designed to equip African Americans with the literacy and numeracy skills necessary for land management, commerce, and civic engagement. These schools also served as community hubs, reinforcing social cohesion and cultural identity amidst a predominantly white settler population.

Land adjudication represented another significant aspect of the Bureau’s work. African American settlers often faced disputes over homestead claims, competing interests from other settlers, and limited access to legal recourse. Bureau agents mediated these disputes, ensuring that freedmen could retain property rights, an essential factor for long-term economic stability. Though resources were limited and enforcement uneven, the Bureau provided critical institutional support, linking federal policy to the practical realities of frontier life and shaping the contours of African American settlement in North Dakota.

African American civil rights laborers in North Dakota engaged in multifaceted activism aimed at combating systemic discrimination and expanding opportunities for economic, social, and political participation. Despite a relatively small population, these activists confronted segregation in schools, discriminatory labor practices, and barriers to political engagement. Churches, fraternal organizations, and mutual aid societies served as central organizing nodes, fostering community solidarity while providing platforms for advocacy and education.

Religious leaders often assumed dual roles as spiritual guides and civil rights advocates. Clergy organized petitions, coordinated educational initiatives, and mediated disputes, effectively serving as both moral and civic authorities within African American communities. Teachers and business leaders similarly contributed to social activism by establishing educational institutions, cooperative enterprises, and communal support networks that strengthened resilience in the face of marginalization.

The activism of African American laborers extended to legal and political engagement. Settlers petitioned territorial and federal authorities to assert land claims, challenge discriminatory ordinances, and secure equitable access to public services.

These efforts exemplify a proactive approach to civil rights that combined grassroots organization with institutional advocacy. Through these activities, African Americans in North Dakota not only resisted oppression but also laid the groundwork for future generations’ civic and economic empowerment, demonstrating the enduring interplay between agency and structural constraint in the post-emancipation period.

The historical experience of African Americans in North Dakota has produced enduring legacies with tangible implications for contemporary society. The settlement patterns, economic strategies, and social institutions established by freedmen shaped the demographic and economic landscape of the state and contributed to the formation of durable community networks. These early initiatives fostered resilience and social cohesion that persist in African American communities, despite ongoing disparities in wealth, education, and political representation.

Modern North Dakota institutions, including universities and corporations, indirectly benefit from historical patterns shaped by slavery and racialized labor, particularly through accumulated capital, land ownership structures, and economic networks originally predicated on exclusion from African Americans in other regions. Recognition of these legacies informs contemporary debates on reparations, equity in education, and targeted economic development initiatives aimed at redressing historical injustices.

Furthermore, the historical trajectories of African Americans in North Dakota provide a lens for understanding contemporary social inequities. Persistent disparities in property ownership, educational attainment, and access to economic opportunity reflect structural continuities rooted in the exclusionary practices of the post-slavery period. By situating modern challenges within this historical context, policymakers, educators, and community leaders can more effectively design interventions that address both historical and contemporary barriers to African American advancement.

North Dakota’s engagement with the legacies of slavery, while often indirect, reveals the complex interplay of structural constraint and individual agency that characterized African American experiences in the post-emancipation United States. From the early presence of individuals such as York to the migration and settlement of freedmen, the state illustrates both the possibilities and limitations of African American life on the northern frontier. Figures such as William Thornton Montgomery exemplify the ways in which agency, entrepreneurial skill, and strategic engagement with federal policy facilitated community formation and economic empowerment, even in regions peripheral to the South.

The intersection of federal initiatives, such as the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Homestead Act, with local legal and social structures, underscores the importance of institutional frameworks in shaping African American experiences. Civil rights laborers, educators, clergy, and entrepreneurs collectively contributed to a legacy of resilience, innovation, and advocacy that continues to influence contemporary social, economic, and political structures in North Dakota.

Understanding the history of African Americans in North Dakota illuminates the broader contours of American slavery and its enduring impact. It demonstrates that slavery’s legacies extend far beyond the South, influencing settlement patterns, economic development, and institutional formation in northern and western territories. Recognizing these connections is essential for both historical scholarship and contemporary policy, offering insights into the structural foundations of inequity and the enduring capacity of African American communities to navigate, resist, and transform the conditions imposed by centuries of racial oppression.

There’s never been a significantly large population of African Americans in North Dakota. But there have been Black people in the state as long as there have been white people. Early records indicate that the earliest Black people came as slaves of explorers and traders. In fact, they were the first non-Native child born here.

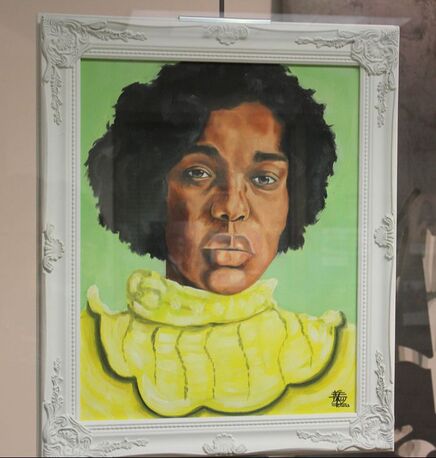

Many also came of their own accord to follow the American dream. One of our most famous North Dakotans was Era Bell Thompson, who became the international editor of Ebony Magazine. She was the daughter of a homesteader near Driscoll who moved to Bismarck in 1919 to run a secondhand store.

Ironically, African Americans had a major advantage over European immigrants — they spoke English. Many had fought in the Civil War, and most had seen enough of the world to know they had a choice of whether to stay here or not; European settlers, on the other hand, were not as aware of their alternatives.

Many African Americans who came to the state were associated with the steamboat trade from St. Louis. Others were in the Army. After the Civil War, many regiments were being relocated out West to provide protection for the railroads, homesteaders and gold-seekers. Many thought that the soldiers wouldn’t be able to withstand the harsh Dakota winters, but General William Sherman, military commander of the West, insisted that troupes sent here be of both races.

In July 1891, two companies of Black soldiers from the 25th Infantry Regiment arrived at Fort Buford on the Upper Missouri, quickly followed by a third. The next summer, two companies from the 10th Cavalry joined them, and by 1893, Fort Buford was made up entirely of these enlisted men; the only whites at the fort were commissioned officers. Native Americans called them buffalo soldiers because their hair reminded them of curly buffalo hair.

They also worked as cowboys. Twenty-two-year-old James Williams worked cattle in the Medora area in 1886, and it’s told that he was such a good roper that he once lassoed a goose right out of midair. Another well-known cowboy was John Tyler, a friend to Teddy Roosevelt.

Of those who came to homestead, William Montgomery is noted for his 1,000-acre bonanza farm south of Fargo. In the Mouse River area, Frank Taylor was a highly respected horse dealer; he had a ranch near Towner where he specialized in raising and trading Percherons and Belgians.

And in sports, North Dakota had integrated baseball teams already in the 1930s. Long before Jackie Robinson broke into the majors, baseball teams all across North Dakota lured, from the Negro Leagues, some of the best players in the world, including legendary pitcher, Satchel Paige.

In short, African Americans may not have settled here in large numbers ... but their contributions have certainly been noteworthy.

Source: Williston Herald

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

Washington D.C.

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

BlackWallStreet.org

Slave Records By State

See: Slave Records By State

Freedmen's Bureau Records

See: Freedmen's Bureau Online

American Slavery Records

See: American Slavery Records

American Slavery: Slave Narratives

See: Slave Narratives

American Slavery: Slave Owners

See: Slave Owners

American Slavery: Slave Records By County

See: Slave Records By County

American Slavery: Underground Railroad

See: American Slavery: Underground Railroad