The history of slavery in the United States is most often narrated in terms of the states where the plantation economy flourished most prominently, where cotton, tobacco, rice, and sugar became synonymous with the forced labor of millions of Africans and their descendants. Nevada, with its arid climate, mining-based economy, and relatively late entrance into statehood in 1864, has often been imagined as peripheral to this system. Yet this perception fails to recognize the complex and often indirect, but nonetheless significant, ways in which Nevada was implicated in the broader structures of American slavery, the slave economy, and the vast slavery industrial complex that undergirded the development of the United States.

An exploration of Nevada’s economic, political, and social evolution from its earliest territorial status through its statehood and into the present day reveals a tapestry of connections to slavery, both material and ideological. These connections included the migration of enslavers and freed people to the territory, the circulation of slave-produced goods and capital, the role of mining corporations and financial institutions in entrenching wealth derived from slavery, and the enduring legacies within Nevada’s institutions of higher learning, political life, and social structures. To understand Nevada’s historical trajectory, one must situate it within the longue durée of slavery’s impact on the American West and the ways in which the state’s industries, policies, and cultural landscape were shaped by forces traceable to the enslavement of Africans and their descendants.

The emergence of Nevada as a territory was already bound up with the fissures of the slavery question. The Compromise of 1850 had created the Utah Territory, which encompassed much of present-day Nevada, and in its legislative architecture allowed the possibility of slavery by leaving the decision to popular sovereignty. This meant that settlers arriving in what would become Nevada were not legally barred from introducing enslaved labor, and while the desert climate and absence of large-scale agriculture made plantation-style slavery impractical, this ambiguity meant that slavery’s legality was not a settled matter.

Indeed, early settlers, particularly those with Southern origins, did bring enslaved African Americans into Utah Territory, and by extension into the lands that later formed Nevada. The Mormon migration westward, central to the peopling of the region, included slaveholding families who saw enslaved African Americans as both spiritual converts and economic assets. The documentary evidence of enslaved people in Salt Lake Valley, some of whom may have traveled or labored in the outlying Nevada frontier, underscores that Nevada was not entirely untouched by the lived presence of slavery.

Nevada’s statehood in 1864, hurried into existence by Abraham Lincoln’s administration to secure votes for the Thirteenth Amendment and bolster Union strength, was emblematic of the contested terrain of slavery’s expansion. The very fact that Nevada was admitted as a free state in the midst of the Civil War tied its existence to the anti-slavery cause, but also to the recognition that the mineral wealth of the Comstock Lode and other mining centers would be critical to financing the Union war effort. This war effort was, in its essence, a conflict over slavery, and Nevada’s economic contribution to the Union treasury meant that the state’s wealth was harnessed in a struggle whose central question was emancipation.

That Nevada’s silver funded the destruction of slavery does not mean that Nevada was innocent of slavery’s legacies; rather, the mining boom that defined Nevada’s economy was enabled by national capital markets that were themselves built upon the profits of enslaved labor. Northern banks, insurance companies, and railroads, many of which financed or insured slaveholding enterprises, invested in the extraction industries of Nevada, meaning that the state’s economic development was linked to slavery-derived capital.

To understand Nevada’s place in the slavery industrial complex, one must look not only at the presence of enslaved individuals but also at the flow of capital, goods, and institutions that carried slavery’s imprint. Slave-produced cotton was the backbone of American and global industrialization, and its profits were reinvested into a wide range of industries, including railroads, mining, and finance.

The railroads that connected Nevada’s mines to broader markets were heavily subsidized by companies and financiers whose fortunes had been made in the cotton trade. Moreover, Nevada’s institutions of higher education, such as the University of Nevada, Reno, while founded after the Civil War, were indirectly sustained by endowments, land grants, and federal allocations whose origins can be traced back to national wealth accumulated during the era of slavery.

The Morrill Act of 1862, which created land-grant universities including Nevada’s, distributed lands expropriated from Indigenous peoples, but it was also underwritten by a federal government whose coffers had long been filled by tariffs on slave-produced goods. Thus, the intellectual and cultural infrastructure of Nevada was implicated in slavery’s legacy even without a large enslaved population within its borders.

The human dimension of slavery’s indirect impact in Nevada can also be traced through migration patterns. African Americans, both enslaved and free, moved westward in the mid-nineteenth century, seeking either opportunity or refuge. Some freed people came to Nevada as laborers in mining towns, where they worked under conditions of discrimination and exclusion, often relegated to the most dangerous and poorly compensated positions.

Others arrived with white settlers, sometimes as servants bound by coercive labor arrangements that blurred the line between slavery and freedom. Nevada’s laws, while not codifying slavery after statehood, nevertheless reflected the racial hierarchies that slavery had entrenched. Black residents faced legal and extralegal barriers to property ownership, employment, and civic participation, a testament to the persistence of slavery’s racial order even in a state nominally committed to freedom.

The absence of formal Freedmen’s Bureau operations in Nevada—since the state had not seceded and did not require Reconstruction oversight—did not mean that freed people were absent from its landscape. Rather, the lack of institutional support for African Americans in Nevada underscored the marginalization they experienced. Without federal resources for education, employment, or civil rights enforcement, Black Nevadans navigated an environment shaped by both the legacies of slavery and the exclusionary dynamics of the frontier.

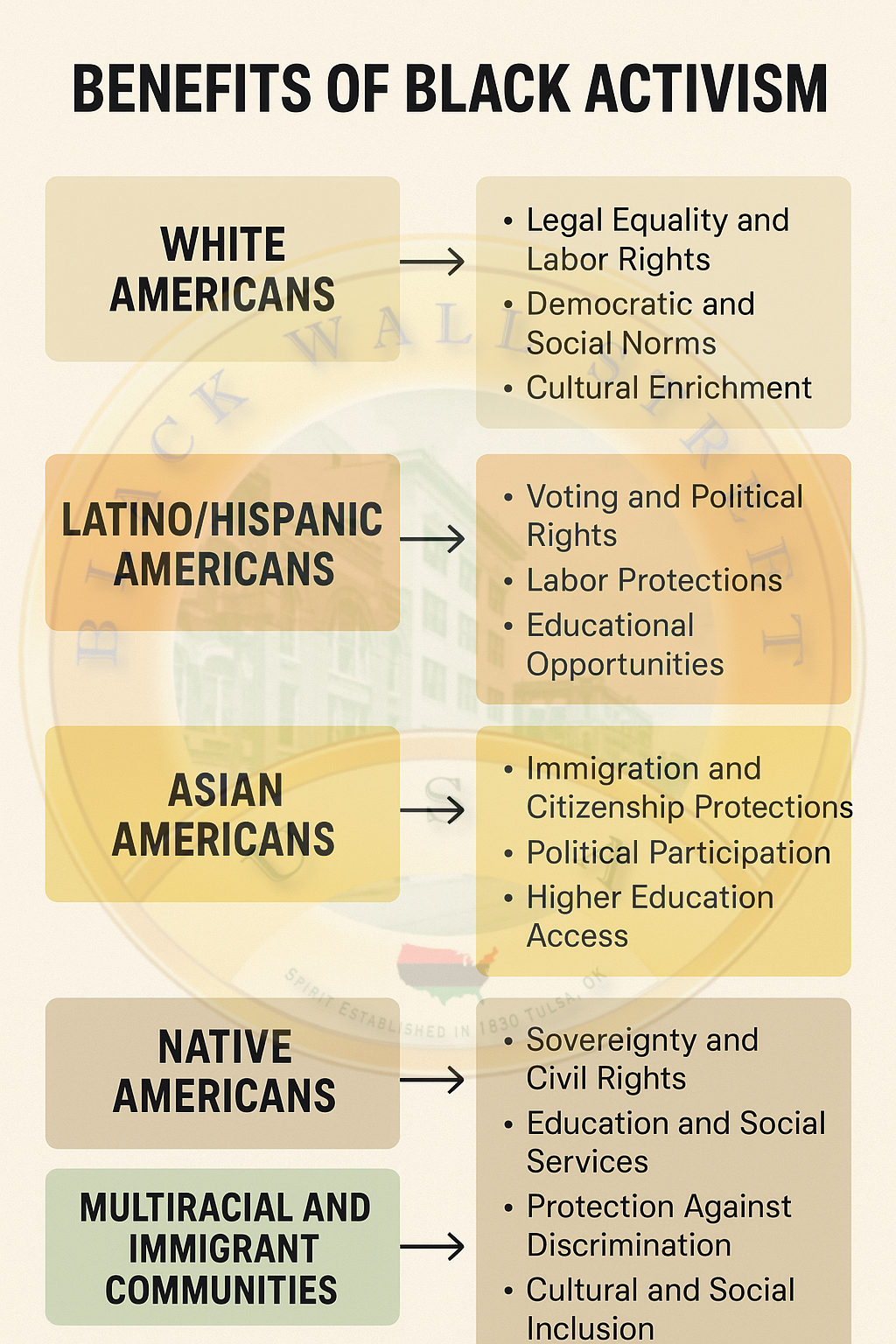

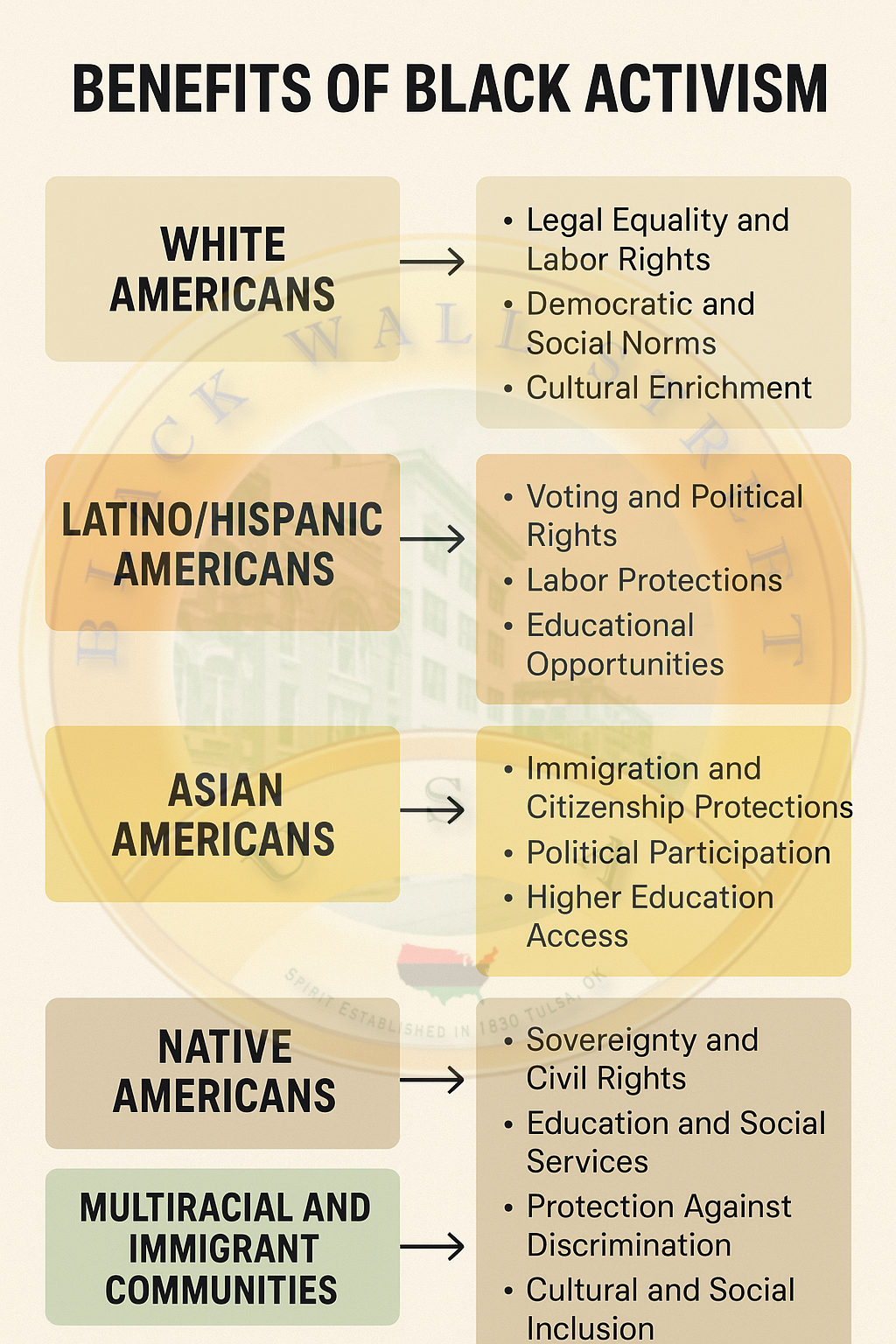

This marginalization laid the groundwork for the struggles of Nevada’s civil rights laborers and freedom fighters in the twentieth century, who confronted systemic discrimination in housing, employment, and public accommodations. Their efforts were part of a continuum of resistance that stretched back to the earliest Black presence in the region, a presence indelibly shaped by the history of slavery.

Notable Black abolitionists from Nevada are difficult to document, in part because the state’s Black population was relatively small in the nineteenth century. However, the absence of nationally famous figures should not obscure the everyday abolitionist practices of Black Nevadans, who resisted subordination through community formation, religious practice, and advocacy for rights.

In the twentieth century, figures such as James McMillan, who became the first African American elected to the Nevada State Senate in 1972, embodied the continuation of the abolitionist struggle in the form of political action and civil rights advocacy. These leaders understood their work as connected to the long shadow of slavery, recognizing that the inequalities they fought were rooted in the racial order slavery had established.

The mining corporations that dominated Nevada’s economy exemplified the entanglement of the slavery industrial complex in new forms. While slavery itself was abolished, the extractive industries relied on labor practices that often replicated the coercion and exploitation of slavery. Chinese immigrant laborers, Mexican workers, and African Americans all endured discriminatory pay scales, hazardous conditions, and exclusion from unions. The profits reaped by these corporations were funneled into national markets where capital derived from slavery still circulated, creating a continuity between antebellum slavery and postbellum capitalism.

Moreover, the speculative culture of mining shares and investments in Nevada mirrored the speculative economy of slaveholding, where enslaved people were treated as collateral and financial instruments. In this sense, Nevada’s economic development perpetuated the logics of commodification and exploitation central to slavery.

The legal structures of Nevada also bore the imprint of slavery’s legacy. While the state constitution prohibited slavery, it also excluded African Americans, Chinese, and Native Americans from certain rights and privileges, revealing how the abolition of slavery did not dismantle white supremacy. These legal exclusions were part of a broader national pattern in which emancipation was followed by new forms of racial subjugation.

In Nevada, this meant that Black residents were denied access to equal education, faced barriers to professional advancement, and were often confined to segregated neighborhoods. The endurance of these structures illustrates how the slave economy’s racial hierarchies were transmuted into post-slavery regimes of exclusion.

The narrative of Nevada’s connection to slavery must also account for the symbolic dimension of state identity. Nevada’s admission as a free state during the Civil War has often been celebrated as evidence of its loyalty to the Union and opposition to slavery. Yet this narrative risks obscuring the ways in which Nevada’s economic and social order was complicit in the broader system that slavery had created.

The silver that fueled the Union war effort was extracted by a racially stratified labor force, financed by capital with roots in slavery, and circulated in markets shaped by the demand for slave-produced goods. To disentangle Nevada from slavery is thus to misapprehend the nature of slavery’s reach: it was not confined to the plantation South but was a national institution whose tentacles extended into every state and territory.

In the modern era, Nevada’s corporations and institutions continue to benefit from structures established during the era of slavery. Casinos, resorts, and real estate developments that define Nevada’s contemporary economy are undergirded by capital accumulation processes that began with slavery. Moreover, universities and cultural institutions in Nevada are only beginning to grapple with their entanglements in this history.

The calls for reparations, historical reckoning, and institutional accountability that have emerged nationwide resonate in Nevada, where acknowledgment of slavery’s indirect legacies is critical to advancing racial justice. The struggles of Nevada’s civil rights activists, from those who challenged housing discrimination in Las Vegas to those who fought for equal access to education in Reno, are part of the unfinished work of abolition—a work that demands recognition of slavery’s imprint on every corner of American life, including the Silver State.

When one surveys the arc of Nevada’s history, from its territorial days to its present, what emerges is a narrative not of slavery’s absence but of slavery’s pervasive and often invisible influence. The Nevada slave economy, while not organized around plantations, was nevertheless entangled with the national slave economy through capital, labor, and ideology. The Nevada slavery industrial complex, manifest in mining corporations and financial institutions, perpetuated the exploitation central to slavery in new forms.

Migration brought both enslaved and free African Americans to Nevada, embedding the state within the demographic shifts slavery engendered. Nevada’s laws and institutions, while formally rejecting slavery, reproduced racial hierarchies rooted in slavery. Its universities, corporations, and cultural institutions were nourished by wealth derived from slavery’s profits. And its abolitionists, civil rights laborers, and freedom fighters carried forward the struggle for liberation in a context shaped by slavery’s long shadow.

Slavery in Nevada, then, was never merely an absence or a peripheral issue. It was an indirect but essential presence, shaping the state’s economy, politics, and society in ways both subtle and profound. To write Nevada into the history of slavery is to recognize that slavery was not a regional anomaly but a national institution whose legacies permeate even the deserts and mountains of the American West. Nevada’s story is a testament to the fact that the struggle against slavery and its afterlives has always been, and remains, a struggle across the entirety of the United States.