Slavery in Kentucky

By the time Kentucky achieved statehood in 1792, slavery had already become deeply embedded in the territory, forming a backbone for agricultural and commercial enterprises that would define the state for decades. The 1790 census enumerated 11,830 enslaved individuals in the region, contrasted with only 114 free Black residents, illustrating the stark imbalance of power and freedom in the early society. Within a few decades, by 1860, the enslaved population swelled to over 225,000, representing nearly one-fifth of Kentucky’s total population. This demographic reality made the state a critical nexus between the Upper South and the Deep South, both geographically and economically, positioning it as a microcosm of the broader American struggle over human bondage.

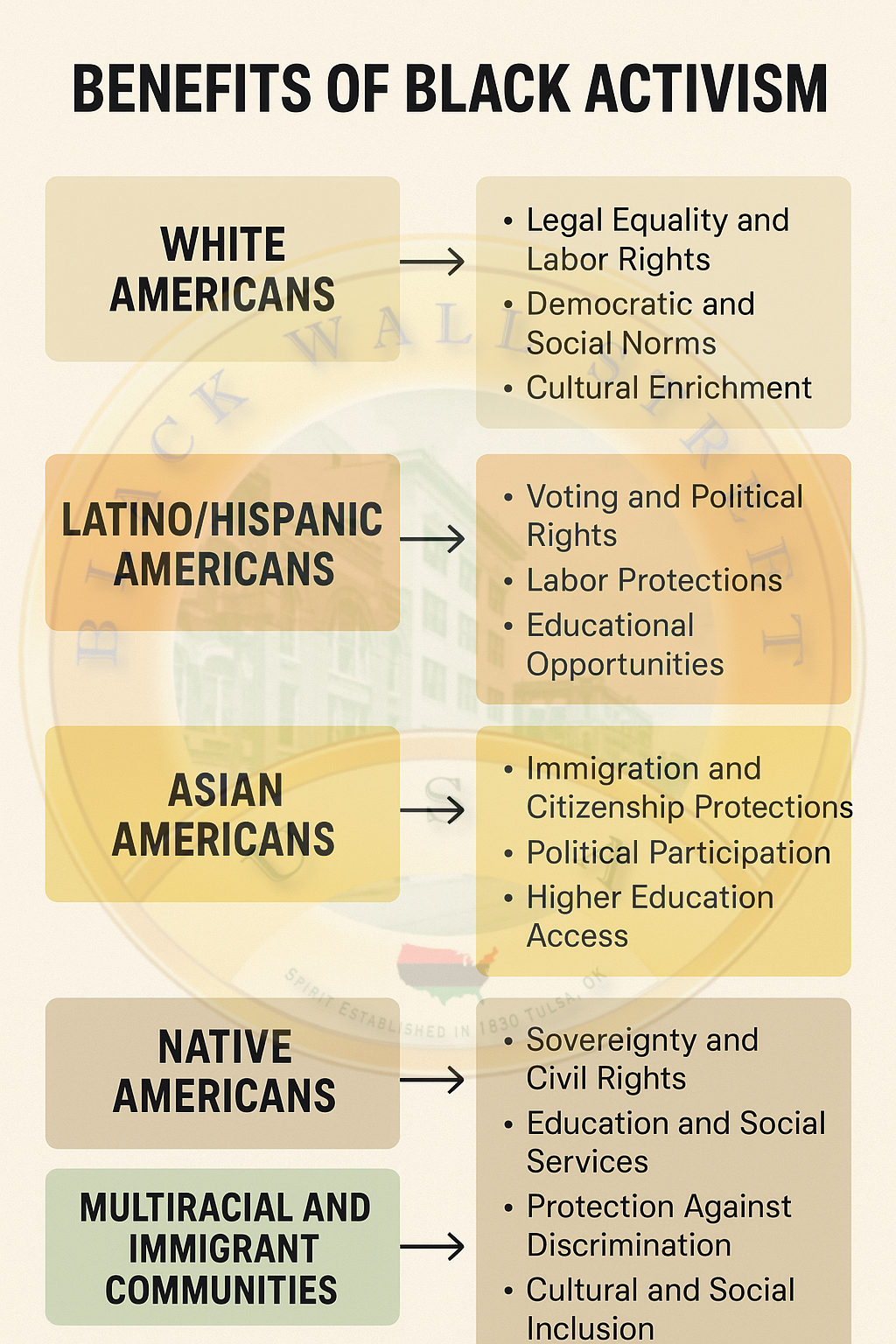

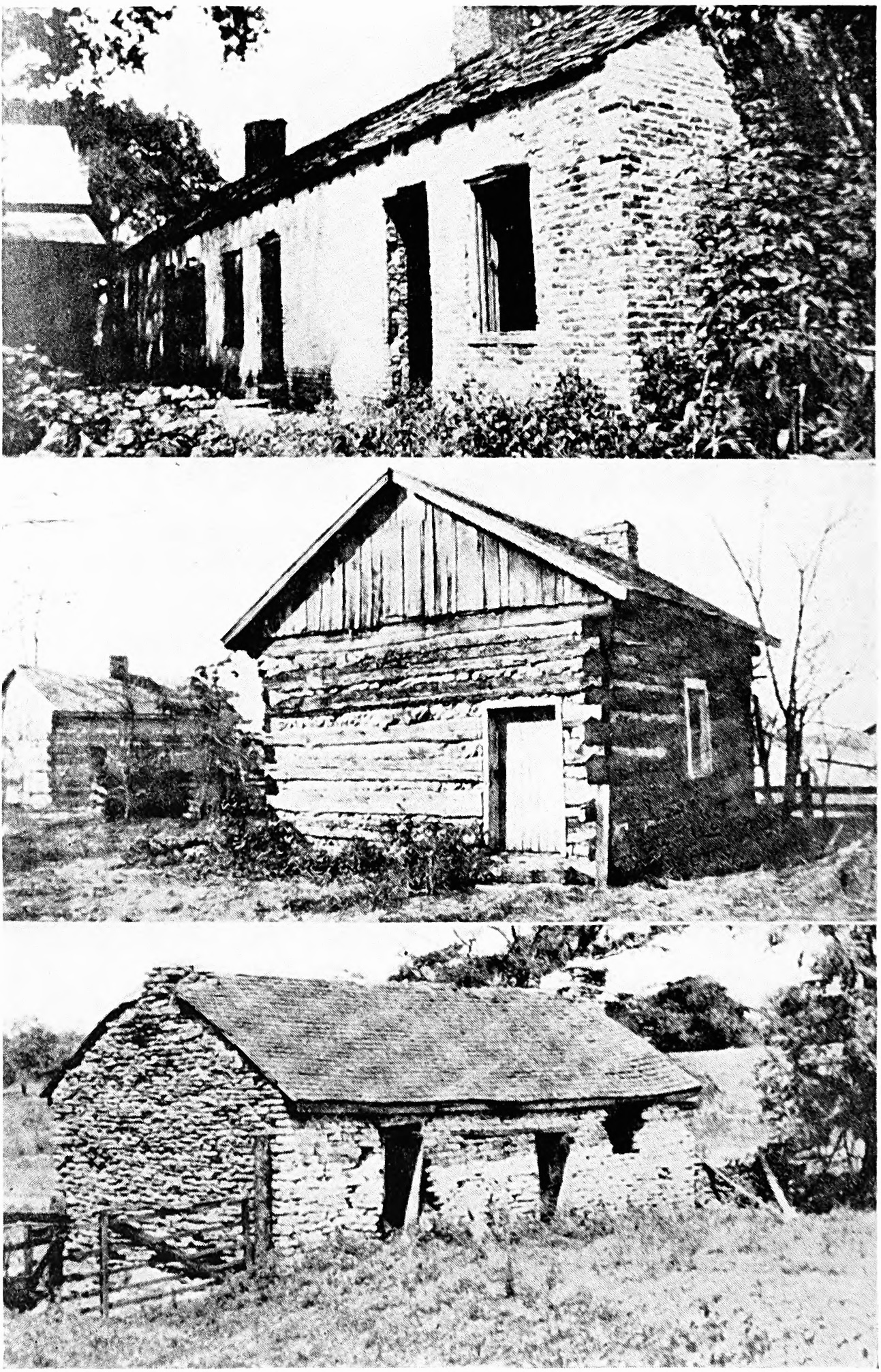

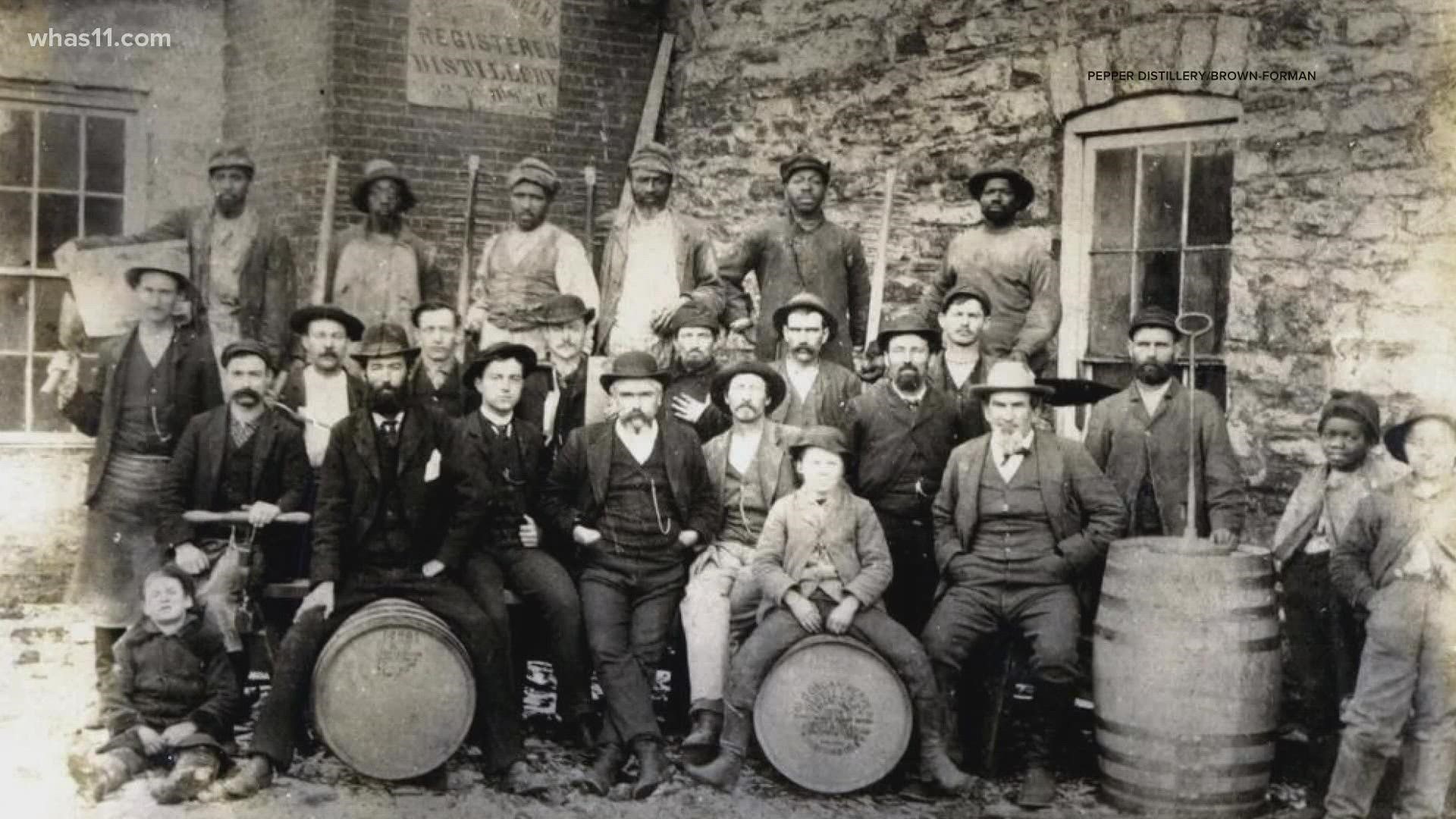

The fertile soil of the Bluegrass region and the temperate climate rendered Kentucky ideal for the cultivation of tobacco and hemp, crops whose profitability relied heavily on the coerced labor of enslaved people. Tobacco plantations, often sprawling estates, required the coordination of hundreds of workers to plant, tend, harvest, and cure the leaves, while hemp, essential for rope and textile production, demanded similarly grueling manual labor. Yet slavery in Kentucky was not confined to agrarian labor alone. Urban centers such as Louisville, Lexington, and Maysville provided venues for enslaved individuals to perform skilled labor in trades, crafts, and domestic service. Blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, and seamstresses among the enslaved population contributed significantly to the urban economy, their labor fueling both local commerce and long-distance trade networks. The dichotomy between urban skilled labor and rural plantation work illustrates the complex integration of slavery into all levels of Kentucky’s economy, reinforcing a social hierarchy that privileged white landowners while reducing Black Kentuckians to commodified human property.

Legally, Kentucky’s embrace of slavery reflected its inheritance of Virginia’s statutes, codifying enslaved people as chattel with no recognized civil or legal rights. The 1792 state constitution adopted Virginia’s slave codes, rendering slaves fully subject to the whims of owners and the state apparatus. Public punishments such as whippings, branding, and even execution for acts of resistance were not uncommon, reinforcing the terror-based social control that underpinned daily life. At the same time, Kentucky’s position as a border state created a nuanced social and political landscape.

Unlike states deep in the cotton belt, Kentucky exhibited both paternalistic justifications for slavery and starkly brutal practices, reflecting tensions between economic necessity, social ideology, and emerging moral opposition. Religious figures, most notably Presbyterian minister David Rice, began voicing anti-slavery arguments as early as the late 18th century, while activists like Cassius Marcellus Clay later advocated for gradual emancipation and colonization, revealing the ongoing moral and political debate surrounding human bondage. Nevertheless, the practical enforcement of slaveholding laws and the economic reliance on enslaved labor ensured that Kentucky remained a deeply entrenched slave society well into the mid-19th century.

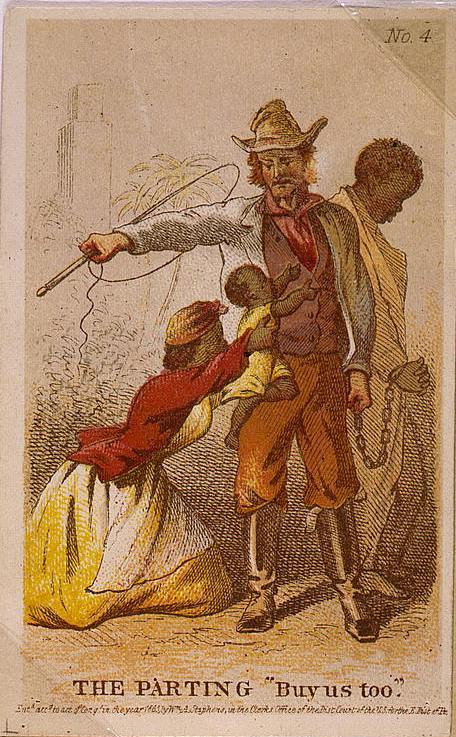

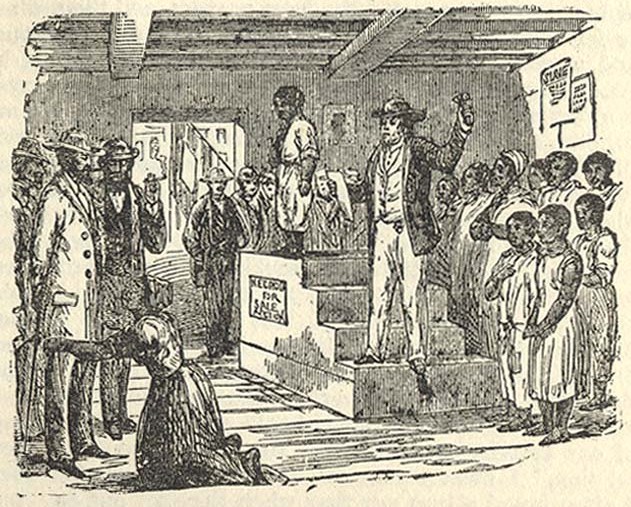

Within this framework, the internal and interstate slave trade flourished. While Kentucky imposed some restrictions on the importation of enslaved people from other states, the internal trade remained vigorous, supplying the labor demands of the Deep South’s cotton plantations. Louisville’s Cheapside Market emerged as a prominent hub, notorious for the sale of “fancy girls” and other enslaved individuals designated for domestic and sexual labor. Traders such as Jordan and Tarlton Arterburn capitalized on these markets, connecting Kentucky to the broader Southern economy and ensuring the circulation of enslaved individuals as both labor and commodity. Beyond the sale of human lives, Kentucky’s enslaved population contributed significantly to wealth accumulation, not only for individual landowners but also for regional banks, transport operators, and other emerging financial institutions, creating the initial structures of what can be understood as a slavery-driven industrial complex.

Resistance to slavery, both subtle and overt, was a constant undercurrent. While mass uprisings were rare due to the pervasive surveillance and threat of violence, escapes and acts of defiance punctuated Kentucky’s history. One of the most significant of these occurred in 1848 when seventy-five enslaved individuals attempted a coordinated escape facilitated by Irishman Patrick Doyle. Although ultimately suppressed, this event highlighted the persistent desire for freedom and the ingenuity required to challenge a deeply entrenched system.

Personal narratives, preserved in part through the WPA Slave Narratives of the 1930s, illuminate the daily realities of bondage and the strategies employed to maintain personal and familial integrity. Ellen Scott of Owensboro, who was freed at the age of twelve, recounted the omnipresence of fear and the constant threat of the lash, emphasizing the psychological as well as physical dimensions of oppression. These narratives reveal not only the brutality of slavery but also the resilience of the enslaved, whose cultural practices, songs, and oral traditions served as instruments of spiritual sustenance and covert communication.

Kentucky’s experience during the Civil War further complicates its history. As a border state, it refused to secede yet resisted federal mandates such as the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1863, the state even codified measures to re-enslave Black individuals who crossed into its jurisdiction seeking freedom, demonstrating the persistence of pro-slavery legal frameworks even amid national conflict. Nevertheless, thousands of enslaved Kentuckians seized the chaos of war as an opportunity for self-emancipation. Estimates suggest that more than seventy percent of the enslaved population fled to Union lines, with approximately 23,703 Black men enlisting in federal service. The military and political choices of these individuals not only undermined the institution of slavery but also positioned Black Kentuckians as active agents in the fight for their liberation, challenging narratives that cast enslaved people as passive victims.

The establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1865 represented a critical intervention during this transition. Under Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, the Bureau assumed responsibility for supervising labor contracts, facilitating family reunification, providing legal protections, and establishing schools for freedpeople. Kentucky’s Bureau field offices, spanning from Bowling Green to Louisville, documented the complexities of emancipation in a society still invested in racial hierarchy. The Bureau faced persistent resistance, including violent backlash, lynchings, and organized attempts to undermine newly established rights. Yet, through these efforts, freed Kentuckians gained literacy, property rights, and a measure of legal recognition that laid the groundwork for post-war social and political mobilization. Court cases and labor disputes recorded in Bureau documents illustrate the enduring struggle for autonomy and the ways in which freedpeople leveraged emerging legal structures to assert their rights.

Equally vital to understanding Kentucky’s journey from bondage to freedom is the role of Black abolitionists and civil rights laborers. Figures such as Henry Bibb, who escaped slavery and became the editor of the “Voice of the Fugitive,” used their experiences to galvanize public opinion and organize networks for the rescue and education of enslaved individuals. William J. Simmons, president of what is now Simmons College of Kentucky, championed educational access as a means of empowerment, emphasizing the intrinsic connection between literacy, civic participation, and liberation. These leaders operated within and beyond Kentucky, connecting local struggles to national movements and shaping the strategies of emancipation, reconstruction, and civil rights advocacy.

The economic and industrial legacies of slavery in Kentucky extended well beyond the immediate abolition of human bondage. Sharecropping and tenant farming replaced the plantation system while perpetuating economic dependency and exploitation. Debt peonage and discriminatory labor contracts constrained Black Kentuckians’ ability to accumulate wealth, while convict leasing programs further perpetuated forced labor, particularly in coal mining, infrastructure, and industrial projects. Wealth generated during slavery, as well as from these subsequent exploitative systems, underwrote the growth of regional banks, transportation networks, and educational institutions. Bourbon distilleries, for example, benefited from enslaved labor both directly, in the cultivation and processing of grains, and indirectly, through the accumulation of capital and local economic structures that perpetuated racialized inequities. The intergenerational transmission of this wealth, coupled with the systemic exclusion of Black populations from these resources, entrenched economic disparities that persist today.

These historical trajectories continue to reverberate in the contemporary era. Corporations and institutions that profited from slavery maintain economic power, and while some have acknowledged historical complicity, concrete reparative measures remain limited. Universities such as the University of Kentucky, banks that insured enslaved lives, and industrial enterprises that leveraged coerced labor remain integral parts of the state’s economic landscape. The structural wealth derived from slavery and post-emancipation exploitation is embedded in urban development, education, and corporate ownership, reflecting the long arc of economic influence. Meanwhile, public memory and cultural recognition of slavery in Kentucky remain contested, with efforts to commemorate, educate, and reconcile often encountering political, cultural, and economic resistance.

Across Kentucky, activists and historians work to excavate and center the experiences of enslaved people and their descendants. Initiatives such as the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, archival projects documenting the WPA Slave Narratives, and community-based educational programs aim to redress historical erasure and promote understanding of the enduring impact of slavery. Renaming of historically significant sites, like Cheapside Park in Lexington, represents an effort to confront past injustices while fostering public acknowledgment of systemic oppression. Organizations such as the Kentucky Black Caucus and local chapters of national movements engage in policy advocacy, public education, and memorialization to link the historical realities of slavery with contemporary struggles for racial and economic justice.

The cultural and spiritual dimensions of slavery also provide essential insight into the lived experience of Black Kentuckians. Enslaved communities developed complex systems of support and resistance, including clandestine education, religious observances, and the maintenance of familial networks despite forced separations. Music, storytelling, and ritual served as mechanisms for preserving identity and instilling resilience, with coded songs functioning both as expressions of hope and as practical tools for escape via the Underground Railroad. These practices underscore the agency of enslaved people, revealing a rich cultural heritage that survived systemic efforts to erase Black autonomy and creativity.

The narrative of slavery in Kentucky is, therefore, a story of intertwined oppression and resilience, of economic structures built on human suffering and communities forged through resistance and ingenuity. The arc from bondage to liberation encompasses not only the physical realities of labor and punishment but also the intellectual, cultural, and political engagements of Black Kentuckians seeking freedom, dignity, and justice. The consequences of these historical processes are both material and psychological, shaping economic disparities, social hierarchies, and cultural memory into the present day.

As Kentucky continues to grapple with its past, the work of uncovering, documenting, and analyzing the legacies of slavery remains critical. Public history initiatives, educational programs, and activist movements contribute to a broader understanding of how slavery shaped the state’s economic and social fabric. The recognition of historical complicity by corporations, universities, and other institutions is an ongoing process, highlighting the complex interplay between historical knowledge, moral responsibility, and contemporary action. The story of Kentucky slavery, with its intersecting narratives of oppression, resistance, and survival, demands a continued, nuanced engagement that centers the experiences of the enslaved and their descendants while challenging structures that perpetuate inequality.

We have further expanded in detailed individual slave narratives, including the lives of women and children, the intersection of slavery with gender and labor hierarchies, the role of Kentucky in the domestic slave trade, and the intricate networks of abolitionist resistance that connected Kentucky to broader national and international movements. This will add depth to today's discussion of cultural practices, the psychological toll of enslavement, and the strategies employed by both enslaved and free Black Kentuckians to navigate, resist, and transform a society structured on bondage.

The story of slavery in Kentucky deepens when we examine the individual experiences of the enslaved, the nuanced social and labor hierarchies imposed upon them, and the interplay between resistance, survival, and cultural continuity. Women, in particular, occupied complex roles within this oppressive system. Female enslaved individuals were subjected not only to grueling physical labor in the fields or as domestic servants but also to sexual exploitation that was normalized within the institution of slavery. Their reproductive labor—bearing and raising children—was exploited economically, as each new generation of enslaved children represented increased property value for owners.

Women like Lucy, whose testimony survives in the WPA narratives, described enduring forced pregnancies, daily back-breaking labor, and the simultaneous task of maintaining households under the watchful eye of owners. Yet, within these constraints, women cultivated cultural and spiritual practices that preserved community and provided subtle forms of resistance, including secret religious gatherings, folk healing, and teaching literacy in defiance of prohibitions. These acts of resilience were not merely survival strategies but constituted a continuous, quiet assertion of humanity and agency in an environment designed to strip it away.

Children, too, experienced the brutality and precarity of slavery in uniquely devastating ways. Families were routinely separated through sales or coercive labor assignments. A child might work alongside their mother in the fields by age six, or serve as a domestic helper in urban households, learning early the mechanisms of social control and surveillance that sustained the institution. Yet even among the youngest, acts of resistance emerged, ranging from small acts of defiance, such as feigning illness or sabotage, to participation in escape attempts. The story of John, an eleven-year-old who fled with his mother during a nocturnal escape facilitated by the Underground Railroad, exemplifies how even children could navigate and subvert the oppressive system with the guidance of community networks and coded knowledge.

Kentucky’s strategic position in the internal slave trade amplified the reach and impact of slavery. Situated along the Ohio River, the state functioned both as a source of enslaved labor for the Deep South and as a transit hub for human trafficking. Traders capitalized on the geographic advantages to transport enslaved individuals to markets in Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana, where the profitability of cotton plantations demanded a constant supply of labor. This trade created a layered economy in which urban merchants, riverboat operators, and insurance companies were economically tied to slavery. Families were fractured as individuals were forcibly relocated hundreds of miles away, yet these movements also facilitated the spread of information, networks of kinship, and knowledge of escape routes. Abolitionist organizations and free Black communities in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois often relied on intelligence from enslaved Kentuckians to coordinate rescues, demonstrating that the interconnectedness of regions both sustained slavery and provided avenues for resistance.

The emergence of organized abolitionist efforts in Kentucky was shaped by these economic and social realities. Figures such as Henry Bibb, a former slave who became a prominent lecturer and publisher, utilized the printed word to expose the cruelties of the system and galvanize local and national opposition. Bibb’s “Voice of the Fugitive” chronicled the experiences of enslaved individuals, providing a platform for testimony that was otherwise silenced. Likewise, Cassius Marcellus Clay, though a white advocate, leveraged his political position to promote gradual emancipation and the colonization movement, establishing Kentucky as a site of complex, contested moral, and political debates over slavery. Black-led churches and mutual aid societies also became critical nodes of resistance and community organization. These institutions fostered education, leadership development, and the cultivation of a political consciousness that would underpin later civil rights labor movements.

The Civil War era further accelerated the dissolution of slavery in Kentucky while exposing the precarious position of Black Kentuckians. Despite the state’s official refusal to secede, military and political pressures created openings for mass self-emancipation. Thousands of enslaved individuals fled to Union lines, often risking capture and punishment. The enlistment of approximately 23,703 Black men into federal service not only contributed materially to the Union effort but symbolically represented an assertion of personhood and citizenship. Military service provided access to wages, education, and networks that would inform post-war activism and community reconstruction. Yet, the war also generated new forms of vulnerability. Escaped slaves who settled near Union encampments faced threats from pro-Confederate sympathizers, disease, and the challenges of securing adequate food and shelter. These dualities—freedom and precarity, agency and threat—define much of the transitional experience for Black Kentuckians in this period.

The Freedmen’s Bureau’s operations in Kentucky, beginning in 1865, offer a window into both the possibilities and limitations of Reconstruction-era reforms. Bureau agents supervised labor contracts between freedpeople and former owners, attempting to ensure fair wages and working conditions, yet enforcement was inconsistent and often undermined by local resistance. Education was a particular focus, as schools were established to teach literacy and vocational skills, essential tools for economic autonomy and civic participation. Family reunification represented another critical aspect of the Bureau’s work. Legal and informal interventions sought to reconnect parents and children torn apart by decades of enforced separation. The Bureau’s field reports, legal petitions, and correspondences provide detailed evidence of the structural challenges in translating freedom into lived reality, illustrating the complexities of transforming social, economic, and political hierarchies that had been firmly established over centuries.

Post-emancipation labor systems perpetuated the economic subjugation of Black Kentuckians despite formal legal freedom. Sharecropping arrangements, tenant farming, and the pervasive use of debt peonage ensured continued control over land and labor. Convict leasing, particularly in industries such as coal mining, rail construction, and urban infrastructure development, constituted a direct continuation of coerced labor, disproportionately affecting Black men. The intergenerational consequences of these systems were profound, contributing to persistent disparities in wealth, property ownership, and access to education. The economic benefits accrued during slavery and subsequent exploitative labor systems became foundational for a range of institutions, including banks, railroads, and industrial enterprises, embedding slavery’s legacy within Kentucky’s modern economy.

Women played a pivotal role in post-emancipation community rebuilding and cultural preservation. Formerly enslaved women organized schools, churches, and mutual aid societies, ensuring that the gains of Reconstruction reached subsequent generations. Figures such as Anna Simms Banks, an educator and community leader, exemplify how Black women leveraged limited resources to create institutions that fostered social cohesion and empowerment. Their work often intersected with national movements for suffrage and civil rights, linking Kentucky’s local struggles to broader agendas of racial and gender justice.

The cultural imprint of slavery in Kentucky extends beyond labor and economics to encompass spiritual, artistic, and intellectual life. Music, particularly spirituals and work songs, conveyed coded messages for escape and survival, reinforced communal bonds, and preserved historical memory. Oral storytelling served not only as entertainment but also as education and resistance, transmitting lessons on navigating oppressive systems, maintaining familial ties, and asserting moral agency. Literacy, often clandestinely acquired, became a powerful tool for both personal empowerment and political mobilization. These cultural practices underscore the active role of enslaved and freed Black Kentuckians in shaping their own destinies and resisting dehumanization.

Modern legacies of slavery in Kentucky remain tangible and complex. Corporations that historically profited from enslaved labor or associated financial instruments continue to operate, often controlling significant economic resources. Universities, banks, bourbon distilleries, and insurance companies benefited directly from the labor, capital, and property accumulated during slavery, and while some have acknowledged historical connections, few have enacted reparative measures commensurate with the scale of exploitation. Wealth disparities, residential segregation, and educational inequities today trace their roots, in part, to these historical structures. The entanglement of economic power, institutional continuity, and racial inequity underscores the enduring consequences of Kentucky’s slavery-based industrial complex.

Public history initiatives, archival preservation, and activist work are vital to addressing these legacies. The Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, local historical societies, and grassroots organizations document and interpret the experiences of enslaved individuals, emphasizing the importance of centering Black voices in historical narratives. Educational programs aim to integrate these histories into curricula, while commemorative efforts—such as the renaming of historically charged sites—serve as tangible acknowledgments of past injustices. Contemporary movements for racial and economic justice in Kentucky are thus inseparable from the historical realities of slavery, underscoring the relevance of past struggles to ongoing efforts for equity and recognition.

The narrative of slavery in Kentucky, therefore, encompasses a vast spectrum: from the daily brutality endured by enslaved individuals, to the strategic resistance enacted through escape, spiritual practice, and organized abolitionism, to the structural economic systems that benefitted from coerced labor, and the ongoing struggle to acknowledge and rectify these legacies. Each story, testimony, and institution forms a thread in the complex tapestry of Kentucky’s history, illustrating the interplay of oppression and resilience, subjugation and agency, memory and justice.

Slavery in Kentucky expands further when considering the lives and contributions of Black abolitionists, civil rights laborers, and freedom fighters, alongside the structural and economic frameworks that sustained bondage and its long-term effects. These individuals not only resisted oppression but actively reshaped the political, social, and economic landscapes of Kentucky and the broader United States.

Henry Bibb stands as one of the most prominent figures in this context. Born into slavery in 1815 in Bourbon County, Bibb escaped captivity in the mid-1830s, eventually settling in Canada, where he became a leading voice in the abolitionist movement. He founded and edited the newspaper Voice of the Fugitive, which chronicled the experiences of enslaved people and provided guidance for those seeking freedom through the Underground Railroad. Bibb’s writing emphasized both the brutality of slavery and the moral imperative for collective action. His work connected Kentucky’s struggles to broader abolitionist networks in the North and internationally, illustrating the interregional and transnational dimensions of resistance. Through his correspondence and lectures, Bibb mobilized public opinion, advocated for legal protections for fugitive enslaved people, and demonstrated the capacity of formerly enslaved individuals to wield intellectual and political authority in shaping discourse about freedom and justice.

William J. Simmons, another seminal figure, played a critical role in post-emancipation educational and community-building efforts. As president of Simmons College of Kentucky, an institution established to provide higher education to Black students, Simmons emphasized literacy, vocational training, and leadership development as foundational tools for empowerment. In the wake of emancipation, education became a battlefield in the struggle for equality. Simmons’ efforts reflect a broader pattern among Kentucky’s Black leaders: leveraging the limited resources available in a segregated society to create institutions that fostered resilience, civic engagement, and intergenerational uplift. Simmons and his contemporaries recognized that economic and political freedom were inseparable from intellectual and cultural agency, and their initiatives laid the groundwork for subsequent civil rights activism.

Other notable abolitionists included John Gregg Fee, a white ally who founded Berea College in 1855 to provide integrated education in Kentucky, and Cassius Marcellus Clay, whose advocacy for emancipation and colonization reflected complex and sometimes contradictory approaches to racial justice. Yet Black Kentuckians consistently navigated these alliances, forming their own strategies for resistance that combined spiritual, educational, and economic initiatives. Mutual aid societies, church organizations, and secret literacy schools offered critical infrastructure for collective advancement, demonstrating how local networks complemented national abolitionist campaigns.

The economic dimension of Kentucky slavery was complex and far-reaching. The state’s reliance on enslaved labor extended beyond agriculture into emerging industrial sectors, transportation networks, and urban enterprises. Tobacco and hemp production provided the initial foundation, but the wealth generated from enslaved labor enabled investment in railroads, banking institutions, and commercial ventures that shaped Kentucky’s economy long after the formal abolition of slavery. The internal slave trade, centered in urban hubs such as Louisville and Lexington, generated significant profit for traders, merchants, and financiers, linking Kentucky to broader Southern markets and creating a proto-industrial complex based on human commodification. Insurance policies on enslaved individuals, mortgages, and financial instruments further entangled white-owned institutions in the economic exploitation of Black labor. These intertwined economic systems created enduring disparities that persist today, illustrating the intergenerational transmission of wealth and power rooted in slavery.

Migration patterns among enslaved and freed Black Kentuckians also shaped the social landscape. During slavery, forced relocation to the Deep South disrupted families and communities, while simultaneously exposing individuals to broader networks of resistance, knowledge, and kinship. Following emancipation, migration continued as freedpeople sought employment, security, and social networks, often moving northward to cities such as Cincinnati, Indianapolis, and Chicago, or westward to burgeoning communities in Kansas and Oklahoma. These movements contributed to the formation of African American urban enclaves, facilitated political mobilization, and reinforced cultural continuity despite the trauma of displacement. The Underground Railroad, both within Kentucky and across state lines, illustrates the spatial dynamics of escape, resistance, and solidarity. Routes along the Ohio River, through remote rural areas, and via safe houses maintained by sympathetic whites and free Black communities created an intricate web that sustained human mobility in the face of systemic oppression.

Slave narratives, particularly those collected during the 1930s by the Federal Writers’ Project, provide indispensable insight into these lived experiences. Individuals such as Lucinda Milliken of Hopkinsville and Reuben Dennis of Christian County recounted not only the physical hardships of slavery but also the emotional and psychological toll of forced labor, family separations, and constant surveillance. Their stories detail the mechanisms of resistance, including work slowdowns, feigned illness, sabotage, and escape attempts, revealing the ingenuity and courage required to navigate a system designed to suppress agency. These narratives also underscore the critical role of communal networks—familial, religious, and social—in fostering resilience and sustaining hope. Songs, coded language, and spiritual practices functioned both as cultural preservation and as tools for survival, linking generations and reinforcing identity amidst systemic dehumanization.

The post-emancipation period saw the continuation of economic and social subjugation through sharecropping, tenant farming, and convict leasing. Sharecropping arrangements, often structured to favor landowners, kept Black Kentuckians in cycles of debt and dependency, limiting economic mobility and access to property ownership. Convict leasing, which disproportionately targeted Black men, effectively perpetuated slavery under a legal guise, particularly in coal mines, railroad construction, and urban development projects. These systems ensured the persistence of racialized labor hierarchies, reinforcing white economic dominance while marginalizing Black laborers. The wealth generated during this era not only benefited individual landowners but also fortified institutions that continue to wield economic influence, including banks, manufacturing firms, and universities.

The role of women during this period was particularly significant. Formerly enslaved women assumed leadership roles within families, religious institutions, and educational organizations. They organized schools, churches, and community groups, providing critical social infrastructure in the absence of state support or equitable resources. Leaders like Anna Simms Banks exemplify this work, demonstrating how women transformed the social and cultural landscape of Black Kentucky communities. Their contributions were foundational in creating pathways for civic engagement, political activism, and intergenerational advancement, bridging the gap between survival under oppression and empowerment in freedom.

Kentucky’s cultural memory of slavery is complex and contested. Public recognition, commemoration, and historical interpretation are uneven, reflecting both the persistence of systemic racism and the ongoing efforts of historians, activists, and community organizations. Efforts to rename Cheapside Park in Lexington, document WPA Slave Narratives, and support heritage education represent tangible strategies to acknowledge and confront this history. At the same time, the economic and institutional legacies of slavery—visible in wealth disparities, residential segregation, and corporate continuity—highlight the ongoing impact of historical exploitation on contemporary social structures.

Spiritual life and cultural expression remained central to Black Kentuckians’ endurance and resistance. Music, dance, storytelling, and ritual provided both solace and strategy, serving as conduits for moral education, coded communication, and collective identity. These practices reinforced resilience, facilitated navigation of oppressive systems, and maintained intergenerational knowledge, linking past experiences to contemporary cultural and political consciousness. The endurance of these traditions underscores the agency of enslaved and freedpeople in shaping their own social realities and resisting systemic erasure.

The interconnection between slavery, economic power, and cultural production in Kentucky exemplifies the broader American experience of bondage and its legacies. Wealth accumulation from enslaved labor created institutions and industries that continue to influence the state’s economic and social landscape. At the same time, Black Kentuckians’ responses—through education, spiritual practice, political activism, and community organization—demonstrate the capacity of oppressed populations to assert agency, resist dehumanization, and shape historical memory.

The historical arc of slavery in Kentucky reaches its full complexity when examining the interwoven economic, cultural, and political legacies that extend into the present, alongside the final set of personal narratives and detailed accounts of resistance, migration, and institutional complicity.

The economic underpinnings of slavery in Kentucky were both expansive and deeply entangled with subsequent industrial development. Tobacco and hemp plantations laid the groundwork, yet the profits accrued were systematically reinvested into urban infrastructure, manufacturing, banking, and transportation. Bourbon distilleries, for instance, were dependent on enslaved labor for the cultivation of corn and rye, the transport of barrels, and the operation of distillation facilities. Families who profited from these industries leveraged slave-produced wealth to establish banks, insurance firms, and real estate portfolios. Some institutions, including major Louisville banks and insurance companies that had underwritten policies on enslaved individuals, became pillars of the local economy, wielding considerable influence into the 20th and 21st centuries. The intertwining of slavery-generated capital with modern financial and industrial systems underscores the persistent structural advantages conferred upon white Kentuckians, highlighting the long-term material consequences of bondage.

Convict leasing, emerging in the late 19th century, extended these patterns of exploitation. Under this system, predominantly Black men were arrested under minor or fabricated charges and leased to private enterprises, often for coal mining, road construction, or urban labor. Conditions mirrored those of antebellum slavery: harsh physical labor, inadequate nutrition, insufficient shelter, and violent discipline were routine. The leasing system functioned as a quasi-legal continuation of enslavement, preserving economic hierarchies while creating profit streams for corporations and government entities alike. Contemporary studies of labor and incarceration in Kentucky trace a direct line from these exploitative practices to mass incarceration patterns today, revealing how the historical economic structures of slavery continue to shape social inequality and systemic oppression.

Migration patterns following emancipation reflected both opportunity and constraint. Freedpeople sought to escape the lingering violence and economic exploitation of the South, often traveling northward along the Ohio River or westward to urban centers and new settlements. Communities in Cincinnati, Indianapolis, and Chicago became hubs of Black cultural, political, and economic life, providing networks of employment, education, and mutual aid. Within Kentucky, rural freedpeople often remained in former plantation regions, negotiating tenancy agreements and labor contracts while confronting ongoing racial hostility and legal restrictions. The juxtaposition of mobility and entrenchment highlights the geographic and social complexities of post-emancipation life, illustrating the nuanced interplay between freedom, risk, and opportunity.

The cultural dimensions of slavery and resistance persisted alongside these economic and geographic realities. Enslaved and freed Black Kentuckians cultivated music, storytelling, dance, and spiritual practice as vehicles for survival, identity, and resistance. Spirituals, in particular, served multiple functions: they were a source of moral and emotional support, a means of clandestine communication, and a repository of historical memory. Oral traditions and storytelling preserved genealogies, historical accounts, and moral teachings, passing knowledge between generations while reinforcing community cohesion. These practices ensured the survival of cultural identity despite systemic efforts to erase it, illustrating the profound creativity, resilience, and agency of Black Kentuckians.

The role of Black women remained central to both cultural preservation and civic leadership. Beyond their work on farms or in urban labor, women organized churches, schools, and mutual aid societies. They provided critical education, spiritual guidance, and social infrastructure, ensuring continuity of community and empowerment in the face of structural obstacles. Leaders such as Anna Simms Banks exemplify how women transformed marginal resources into institutional power, shaping the social and cultural trajectories of their communities. These contributions underscore the gendered dimensions of resilience and activism in Kentucky, highlighting how women navigated and reconfigured the legacies of slavery to create enduring community strength.

Kentucky’s Black abolitionists and civil rights laborers continued to exert influence long after emancipation. Figures like William J. Simmons and Henry Bibb laid the foundation for subsequent generations of political, social, and educational activism. Their work in schools, newspapers, and religious institutions cultivated literacy, civic participation, and political consciousness, empowering communities to navigate post-emancipation challenges. These networks facilitated resistance to voter suppression, economic exploitation, and social marginalization during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era. The activism of Black Kentuckians was both local and national, connecting to broader movements for civil rights, labor reform, and social justice, demonstrating the sustained impact of leadership rooted in the struggle against slavery.

Modern corporate and institutional legacies of slavery in Kentucky remain visible today. Universities, banks, bourbon distilleries, and manufacturing firms that historically benefited from enslaved labor continue to wield significant economic and social influence. While some have acknowledged historical connections, most have not enacted reparative measures commensurate with the scale of exploitation. Wealth disparities, educational inequities, and residential segregation reflect the intergenerational impact of these historical structures. Organizations such as the University of Kentucky and local banks trace institutional wealth to assets and labor extracted from enslaved individuals, highlighting the embedded nature of slavery’s economic influence in contemporary society.

The preservation and interpretation of Kentucky’s slavery history are critical for contemporary understanding and justice. Archival projects, educational initiatives, and community activism aim to recover the voices of enslaved and freedpeople, ensuring that their experiences are recognized and honored. The Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, historical societies, and grassroots organizations document narratives, commemorate historical sites, and facilitate public education. Renaming Cheapside Park in Lexington, preserving field office records of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and promoting heritage education programs are part of ongoing efforts to confront the legacies of slavery while fostering civic engagement and historical awareness.

The personal narratives collected in the WPA Slave Narratives provide unparalleled insight into the lived experience of slavery in Kentucky. Accounts from Lucinda Milliken, Reuben Dennis, and countless others convey the physical, psychological, and emotional dimensions of bondage, the strategies of resistance employed, and the enduring human spirit that survived oppression. These testimonies illuminate the systemic nature of slavery while foregrounding individual agency, courage, and resilience. Collectively, they form a vital archive for understanding the human consequences of slavery and the ongoing work required to address its legacies.

Kentucky’s history of slavery is both a testament to human cruelty and a chronicle of resilience, resistance, and transformation. From the earliest settlement to the contemporary reckoning with economic and social legacies, the state’s story encompasses the brutality of bondage, the ingenuity and courage of those who resisted, and the ongoing consequences for communities and institutions today. The structural and cultural imprints of slavery persist in wealth disparities, corporate power, educational inequities, and social stratification, yet they coexist with a rich heritage of activism, cultural preservation, and community-building. The narrative of Kentucky slavery is thus one of continuity and change, oppression and agency, memory and justice—a story still being written through ongoing scholarship, activism, and public engagement.

By integrating economic analysis, detailed slave narratives, migration studies, the work of the Freedmen’s Bureau, biographies of Black abolitionists and civil rights laborers, and an examination of modern institutional complicity, BlackWallStreet.org reaches a comprehensive synthesis of the Kentucky slave experience. This situates historical slavery not as an isolated past but as a continuum influencing present social, economic, and cultural structures, emphasizing the enduring need for historical accountability, community remembrance, and systemic reform.

Kentucky Slavery Study Guide

Slavery was a part of Kentucky from the time of its earliest European settlements until the end of the Civil War. The first Kentucky constitution in 1792 protected the interests of Virginia gentry who owned land and slaves, and slavery was formally legalized in the state's constitution. Article IX of the constitution stated that slavery could only be abolished by the owner's consent or through compensated emancipation.

Slaves in Kentucky worked in many different ways, including: On small farms with their owners, Building infrastructure, Cultivating tobacco and hemp, As house servants, and In factories. In 1830, enslaved African Americans made up 24% of Kentucky's population, but that number had dropped to 19.5% by 1860. In 1833, Kentucky passed a law that prohibited the sale of slaves brought into the state from other places.

While some people objected to slavery on moral or religious grounds, anti-slavery efforts in later years were often symbolic and focused on colonization, or removing free African Americans. Kentuckians have helped, hindered, and fought for and against slavery throughout history, and enslaved people have sought freedom from the beginning. Slavery was ultimately outlawed in the United States by the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

From the earliest settlement of Kentucky through the tumult of the Civil War and into the present-day reckoning, slavery shaped every facet of life—from agriculture and trade to law, culture, and resistance. This article embarks on a sweeping journey through the origins of slavery in Kentucky, its economic underpinnings, the harrowing personal narratives of the enslaved, and the enduring legacies that surface today. Though its roots run deep, this story is not static; it pulses with the efforts of freedpeople, abolitionists, civil rights laborers, and corporate complicity that endures in subtle and overt forms.

Slavery arrived in Kentucky before it officially became a state in 1792, brought westward by settlers carrying human bondage as essential Southern currency. By 1790, there were approximately 11,830 enslaved individuals in the region and 114 free Black people, a figure that swelled to over 225,000 enslaved persons—19.5% of the population—by 1860. The bulk of these enslaved people worked tobacco and hemp plantations in the fertile Bluegrass region, but those near Louisville or along the Ohio River often labored in skilled trades or domestic roles. Yet Kentucky was a border state—a hybrid nation in microcosm. Legally slaveholding, economically tied to both North and South, the state maintained a cultural duality: some viewed slavery as mild and paternalistic, while others experienced its brutal realities, including public whippings and executions for resistance. Under the 1792 constitution, Virginia's slave laws were adopted, branding enslaved people as real estate with virtually no rights.

Despite occasional moral opposition—voices like Presbyterian minister David Rice, active abolition societies in the early 1800s, and gradual emancipation proponents like Cassius Marcellus Clay—Kentucky’s efforts often veered toward colonization instead of integration. Laws banning the interstate import of slaves surfaced as early as 1833, yet the internal trade thrived. Louisville’s Cheapside market became infamous, especially for "fancy girls" sold into sexual servitude. Traders such as Jordan and Tarlton Arterburn profited substantially from the deep South’s growing cotton economy, returning many enslaved Kentuckians to the Lower South.

Enslaved individuals navigated this world with extraordinary resilience. In 1848 a mass escape of 75 people—facilitated by Irishman Patrick Doyle—marked the largest single slave uprising in Kentucky history. Although suppressed, dozens gained their freedom when others fled into woodland and beyond. Personal testimonies pierce the abstractions. Ellen Scott, freed in Owensboro at age 12, later recounted: “We had not been taught to have feelings, except fear… There was but one thing we thought of. It was the lash, the horrible way it whistled on our backs…” Across the state, records of coffles, slave pens, and harrowing escapes are well documented in field offices now preserved by the Freedmen’s Bureau.

When the Civil War erupted, Kentucky refused to secede, though its legislature resisted the Emancipation Proclamation. In 1863, the state even passed laws enslaving any Black person crossing into its territory seeking freedom. Yet more than 70% of enslaved Kentuckians self-emancipated or fled to Union lines; around 23,703 Black men eventually enlisted in federal service. The Freedmen’s Bureau—established March 3, 1865—arrived as both relief and reform. Under Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, the Bureau supervised labor contracts, reunited families, legalized marriages, built schools, and prosecuted violent agitators. Field Office records from Bowling Green to Louisville unveil labor disputes, legal testimonies, and violent backlash—including lynchings and “injunction” groups targeting freedpeople. These documents now illuminate the remarkable transitions from slavery to freedom.

This early arc from Kentucky’s legal adoption of slavery to its formal abolition on December 18, 1865, via the Thirteenth Amendment—despite being ratified by Kentucky only in 1976—sets the stage for the post-war reconstruction efforts and the courageous people who refused to remain silent. Central to that silence-breaking were Black Kentuckians who organized politically and socially. From William J. Simmons, president of what is now Simmons College of Kentucky, to the writings of Henry Bibb, who escaped slavery and became a leading abolitionist and publisher of the "Voice of the Fugitive," Kentucky’s Black voices brought national attention to the injustices inflicted both during and after slavery.

Many former slaves contributed narratives to the WPA Slave Narrative Collection in the 1930s. These firsthand accounts, like that of Lucinda Milliken from Hopkinsville, or Reuben Dennis of Christian County, painted a vivid picture of daily life, family rupture, hunger, religious hope, and resistance. Their oral testimonies are not merely reflections of suffering but declarations of survival. Through these, we learn how songs, prayer meetings, and folk tales acted as tools of spiritual resistance and how coded language guided the Underground Railroad.

The economic machine that slavery built in Kentucky outlived slavery itself. Sharecropping replaced the plantation in structure but not in subjugation. Black Kentuckians were often locked into debt peonage, denied fair wages, education, and political rights. Violence and voter suppression were common during Reconstruction and into the Jim Crow era. Convict leasing through prisons like the Kentucky State Penitentiary re-enslaved Black men, especially for coal and infrastructure projects. Wealth generated from this system enriched corporations and individuals who later invested in banks, railroads, and manufacturing.

Fast-forward to today and the fingerprints of the slavery industrial complex remain. Corporations that profited from slavery continue to operate, some having issued apologies but rarely reparations. Institutions such as the University of Kentucky and prominent bourbon distilleries benefited from enslaved labor in their founding and growth. Louisville banks that underwrote slave insurance policies still hold major financial power. These linkages are not just historical footnotes but economic DNA encoded into the wealth gaps that exist today.

Across Kentucky, movements for historical justice are gaining ground. The renaming of Cheapside Park in Lexington, the work of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, the efforts of groups like the Kentucky Black Caucus and Black Lives Matter Louisville—all are part of a renewed effort to confront and repair the legacies of slavery. Educators, genealogists, and youth organizations now collaborate to unearth buried histories and return agency to Black voices suppressed for generations.

In closing, Kentucky’s story is not merely one of complicity but also of confrontation and courage. It is the story of resistance against a powerful system, the endurance of the human spirit, and the continuing struggle for justice. From the shadows of Cheapside to the halls of policy-making, from the silence of archives to the rallying cries in the streets, the arc from slavery to freedom in Kentucky is neither complete nor forgotten. It is still being written.

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

BlackWallStreet.org

Slave Records By State

See: Slave Records By State

Freedmen's Bureau Records

See: Freedmen's Bureau Online

American Slavery Records

See: American Slavery Records

American Slavery: Slave Narratives

See: Slave Narratives

American Slavery: Slave Owners

See: Slave Owners

American Slavery: Slave Records By County

See: Slave Records By County

American Slavery: Underground Railroad

See: American Slavery: Underground Railroad