The territory that would become the state of Oklahoma possesses one of the most complex and deeply entangled relationships with the institution of slavery in the United States. Long before the establishment of Oklahoma as a formal state in 1907, its land was at the center of competing forces of settler colonialism, Indigenous sovereignty, racial subjugation, and economic exploitation.

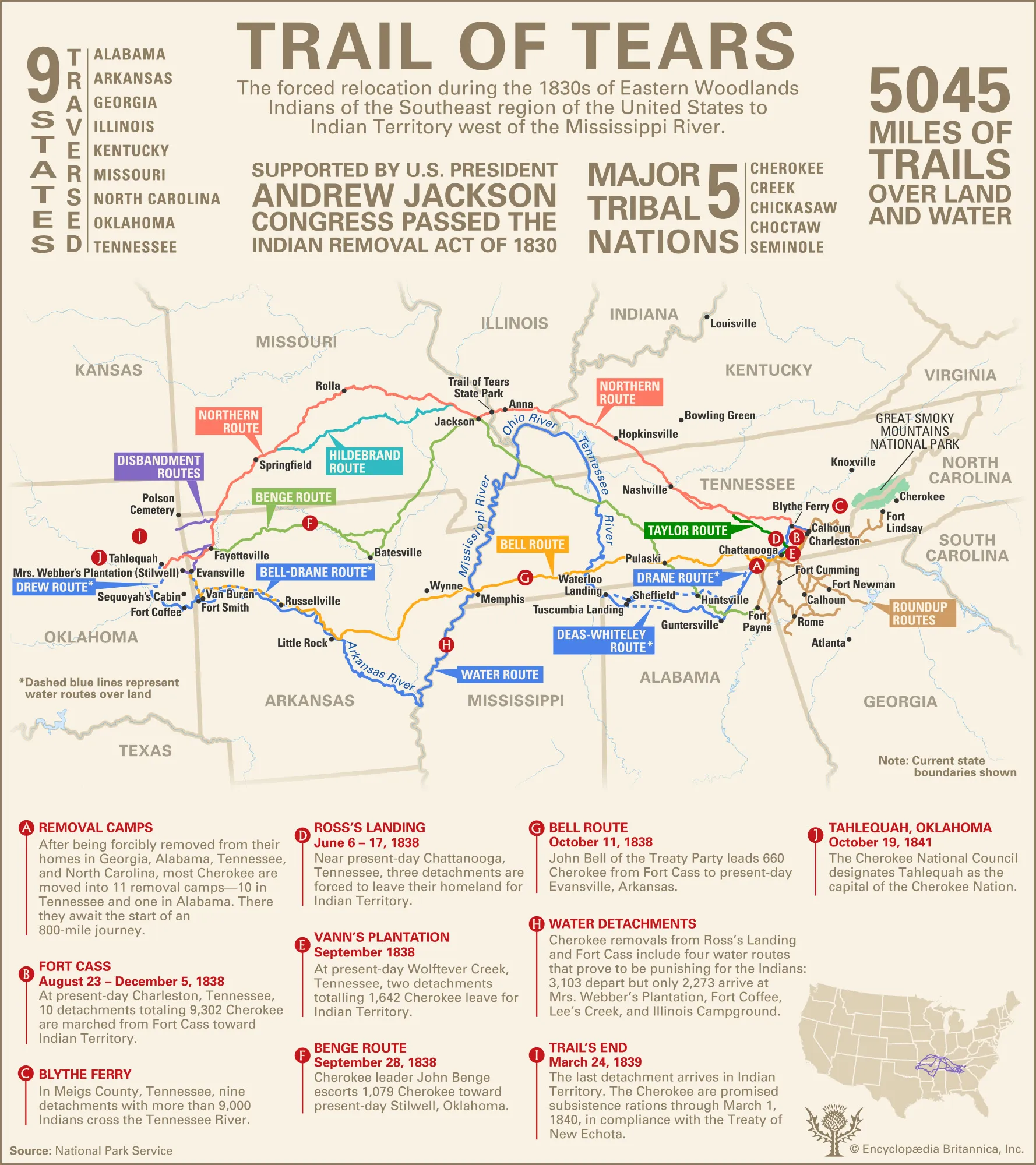

These forces gave rise to a unique and often obscured narrative of enslavement in which Native American nations, African-descended peoples, and white settlers became enmeshed in a brutal tapestry of coerced labor, land dispossession, and intergenerational trauma. At the core of this history stands the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the subsequent Trail of Tears, events that facilitated the transplantation of slavery into the region and gave rise to an enduring “slavery industrial complex” within Indian Territory.

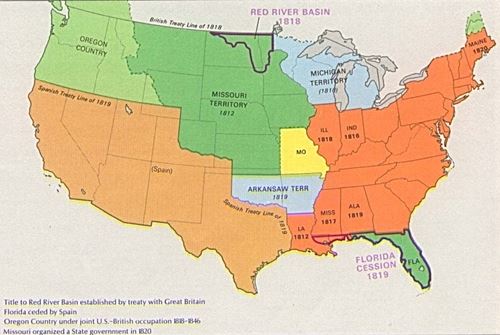

The Indian Removal Act of 1830, a piece of legislation signed into law by President Andrew Jackson, authorized the federal government to negotiate the relocation of Native American tribes from their ancestral homelands in the southeastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River. The moral and legal violence of this act catalyzed a forced migration that would result in the displacement of tens of thousands of Native Americans, including the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek (Muscogee), and Seminole nations. Along with their belongings, livestock, and communal institutions, these tribes brought with them another human cargo: enslaved Africans.

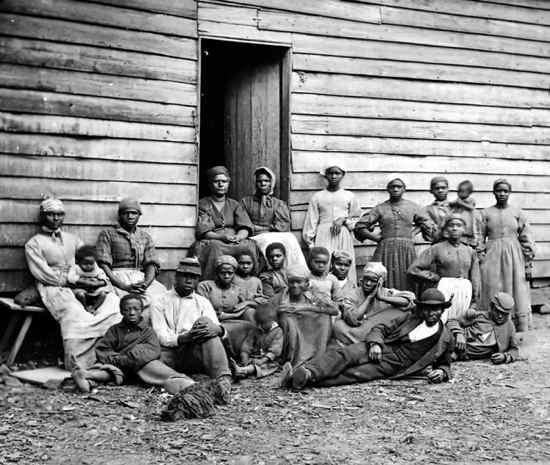

By the early 19th century, several of the so-called "Five Civilized Tribes" had adopted chattel slavery not only as a means of agricultural labor but also as a symbol of "civilization" as defined by the dominant white American society. The adoption of plantation slavery by tribal elites served as a strategy of survival and social mobility within the colonial logic imposed by U.S. power. However, this accommodation did not protect them from eventual dispossession and ethnic cleansing. As these tribes were relocated along brutal and deadly journeys that came to be known collectively as the Trail of Tears, the enslaved African men, women, and children within their communities were forcibly marched as well, enduring the same hunger, exposure, and cruelty that claimed the lives of thousands.

The presence of African-descended slaves within Native societies in Indian Territory—what would eventually become Oklahoma—created a set of hybrid institutions and cultural dynamics that diverged from, yet often mirrored, Southern plantation slavery. Slaveholding among Native tribes was concentrated among elite families, and the conditions of bondage varied widely depending on the cultural practices of each nation. In some contexts, enslaved people were afforded a modicum of integration into tribal life, especially when compared to the rigid racial segregation of the American South. However, in practice, many enslaved Africans were subjected to backbreaking labor, severe punishment, forced breeding, and systemic efforts to erase their African identities.

The economic infrastructure that developed in Indian Territory during the antebellum period increasingly mirrored the plantation economy of the Deep South. Wealthy Native planters, particularly among the Cherokee and Choctaw, operated large-scale farms worked by enslaved labor. Cotton and tobacco emerged as primary cash crops, and these were marketed through white-controlled channels in neighboring states and territories. In this way, the developing economy of Indian Territory became enmeshed in the broader transnational web of the American slavery industrial complex. Native slavery was not an isolated phenomenon; it was integrated into the expansionist ambitions of the United States and facilitated by the same financial, logistical, and ideological frameworks that supported white Southern slavery.

The Civil War would bring this entanglement into stark relief. As conflict erupted between Union and Confederate forces, the Five Tribes found themselves bitterly divided. Many of the tribal elites, whose economic fortunes were tied to slavery, sided with the Confederacy. In return, the Confederacy offered formal treaties that recognized tribal sovereignty and guaranteed the protection of their slaveholding rights. These alliances, however, came at a devastating cost.

Indian Territory became a theater of war, plagued by military incursions, guerrilla warfare, and mass displacement. Entire towns were razed, and tribal cohesion was shredded by internal divisions and external pressures. Enslaved Africans, caught in the crossfire, faced increased surveillance and violence, while many used the chaos of war to escape bondage and seek freedom among Union lines or within maroon communities.

Following the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865, the U.S. government imposed new treaties on the Five Tribes as a condition of reconstruction. These treaties mandated, among other things, the abolition of slavery and the granting of citizenship and land rights to freedmen—former slaves of the tribes. However, the implementation of these promises was inconsistent and fraught with resistance. Tribal governments often sought to limit or rescind the rights of freedmen, setting the stage for over a century of legal battles and racial exclusion that persists even into the present. The federal government, too, failed to uphold its commitments, often prioritizing white settler interests over the rights of both Native and African-descended peoples in Indian Territory.

The late 19th century witnessed a transformation in the economic and political landscape of what would become Oklahoma. As the frontier closed and white settlers pressed into Indian Territory through land runs, allotments, and outright seizure, the foundations of the slavery industrial complex were repurposed to support a new regime of racial capitalism. Former plantations were converted into farms, mines, and oil fields worked by Black sharecroppers and wage laborers whose economic options remained constrained by systemic racism. Freedmen’s descendants, despite formal emancipation, found themselves trapped in a cycle of debt, land theft, and racial violence, mirroring the fates of freedpeople across the American South.

The establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau in the aftermath of the Civil War brought some measure of relief and education to formerly enslaved people in Indian Territory. The Bureau established schools, negotiated labor contracts, and sought to protect the legal rights of freedmen. However, its impact in Oklahoma was limited by the jurisdictional ambiguities created by tribal sovereignty and the broader federal neglect of Indian Territory. Many freedmen found themselves in a legal limbo, simultaneously excluded from tribal citizenship and denied full recognition by the federal government. The collapse of the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1872 left many communities vulnerable and without institutional support.

Despite these challenges, African-descended Oklahomans forged vibrant communities rooted in mutual aid, education, and resistance. Black towns such as Boley, Langston, Clearview, and Rentiesville emerged as symbols of self-determination and racial pride. These towns were often founded by freedmen and their descendants, who sought refuge from white supremacy by building independent economic, religious, and political institutions. Yet even in these spaces, the legacy of slavery cast a long shadow. Land ownership remained precarious, economic opportunities were constrained, and white hostility often erupted into violence, most notably in the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

The destruction of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, known as “Black Wall Street,” serves as a brutal reminder that the legacy of slavery in Oklahoma did not end with emancipation. The massacre, in which a prosperous Black community was bombed, looted, and burned by white mobs with the complicity of law enforcement and the National Guard, represents the continuity of racial terror and economic suppression born of slavery. Many of the families affected were descendants of Oklahoma freedmen, whose attempts to escape the vestiges of bondage through entrepreneurship and education were met with genocidal violence. The silence and denial that followed the massacre further entrenched the invisibility of Black suffering in the historical narrative of Oklahoma.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the ghost of slavery continues to shape the racial, economic, and educational landscape of Oklahoma. Institutions of higher learning, such as the University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma State University, owe aspects of their development to land grants derived from Native and freedmen lands, a process enabled by federal policies rooted in settler colonialism and the aftermath of slavery. These institutions have often failed to adequately acknowledge their complicity or to make meaningful reparations. Likewise, major corporations operating in Oklahoma—particularly in oil, agriculture, and rail—benefited from the exploitation of Black labor and the dispossession of Native land, perpetuating a system of racialized wealth extraction.

While much of the national discourse around slavery centers on the Southern plantation states, Oklahoma presents a compelling and urgent case for expanding the historical frame. Here, slavery was not merely an imported institution but a foundational element in the creation of the state’s political economy, social hierarchy, and cultural landscape. The interweaving of Native dispossession and African enslavement in Oklahoma reflects a uniquely American form of settler-slave colonialism, in which multiple forms of racialized domination converged and reinforced one another.

This complex inheritance continues to provoke legal and moral reckonings. Ongoing lawsuits by descendants of freedmen seeking tribal citizenship, reparations movements for the descendants of Greenwood, and the struggle for historical recognition underscore the unfinished business of emancipation in Oklahoma. These efforts challenge the state—and the nation—to confront the full scope of its entanglement with slavery and to envision a more just future rooted in truth, accountability, and repair.

As Oklahoma transitioned from a contested and colonized territory into a structured legal and economic system under U.S. governance, the conditions of formerly enslaved African-descended peoples in the region underwent a shift that was not synonymous with liberation. The abolition of slavery in the Indian Territory, codified in post-Civil War treaties between the federal government and the Five Tribes, provided only a nominal form of emancipation. True self-determination remained elusive. Although legal slavery had ended, the mechanisms of control, exploitation, and racial hierarchy simply evolved. These new mechanisms formed the postbellum dimension of the slavery industrial complex—a system in which Black labor continued to be commodified, surveilled, and exploited through peonage, tenant farming, incarceration, and systemic educational deprivation.

The early Reconstruction period in Indian Territory was marked by legal battles over the political status of freedmen. The 1866 treaties mandated that the Five Tribes recognize freedmen as full members, with equal rights to land and citizenship. While some tribes implemented these terms—often under duress or reluctantly—others resisted or subsequently attempted to expel freedmen from tribal rolls. This resistance revealed the unresolved contradictions between Indigenous sovereignty, tribal nationalism, and the racial stratification inherited from settler colonialism. The conflict over freedmen’s rights exposed the deep scars slavery had inflicted not only on the bodies and families of the enslaved, but also on the moral foundations of the societies that had held them captive.

The Freedmen’s Bureau, created in 1865 to assist formerly enslaved people across the South and Indian Territory, offered some initial relief. Schools were erected in Muskogee, Fort Gibson, and other parts of the territory, offering rudimentary education to formerly enslaved children and adults alike. Freedmen teachers, many of whom were formerly enslaved themselves, became beacons of hope and advancement in communities where literacy had once been criminalized. However, the scope of the Bureau’s work was limited by funding, jurisdictional complexities, and violent opposition from white settlers and tribal factions opposed to freedmen inclusion. The withdrawal of federal oversight in 1872, when the Bureau was officially dismantled, left freedmen communities without institutional protection or economic support in a region already marked by instability and racial animus.

In the decades that followed, Oklahoma’s Black population—comprised largely of freedmen and their descendants—pursued survival through agricultural labor. Many became sharecroppers and tenant farmers on land they once worked as slaves, now leased under exploitative arrangements. The rise of industrial agriculture in Oklahoma coincided with a wave of corporate and government collusion that made Black economic independence nearly impossible. Railroad companies, many funded by federal land grants and speculative capital, carved tracks across former tribal lands and uprooted entire communities of freedmen. Oil and mineral companies, including Phillips Petroleum, Sinclair Oil, and later Conoco, began extracting wealth from under Indigenous and freedmen land without providing equitable employment, compensation, or royalties to Black laborers or landowners. In many instances, Black and freedmen landholders were deceived into selling their property for far below market value or were violently forced off their land through vigilante actions, legal trickery, or outright arson.

The Dawes Act of 1887 and the Curtis Act of 1898 further eroded communal landholding among the Five Tribes and created a legal architecture for land allotment that proved disastrous for freedmen and tribal members alike. Under the guise of promoting individual property ownership, the U.S. government imposed a system that atomized communal land, undermined tribal governance, and accelerated land loss to white settlers. The Dawes Rolls, which categorized individuals as “freedmen,” “Indians by blood,” or “intermarried whites,” codified racial hierarchies and bureaucratic exclusion. Many freedmen found themselves on separate rolls that did not confer full tribal rights or access to natural resources. These divisions have had long-lasting consequences, including current disputes over tribal citizenship and benefits.

Despite these challenges, African-descended communities in Oklahoma displayed remarkable resilience. A unique aspect of Black life in Oklahoma during the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the proliferation of all-Black towns—more than fifty at the height of the movement. Towns such as Boley, Redbird, Taft, Tullahassee, and Langston were founded by freedmen and their descendants who aspired to create safe havens from the violence and discrimination that plagued mixed and white-dominated areas. These towns featured Black-owned banks, newspapers, schools, churches, and municipal governments. They embodied a radical assertion of autonomy and a direct challenge to white supremacy. Black Oklahomans were building lives outside the shadow of their oppressors, reconstituting family, spiritual life, and economic ambition on land that once symbolized bondage.

Langston University, established in 1897 as the Colored Agricultural and Normal University, stands as a testament to the intellectual and cultural aspirations of Oklahoma’s Black population. As the only historically Black college in Oklahoma, Langston became a center for Black scholarship, agricultural training, and civic leadership. It drew students and faculty from across the region and contributed to a cultural renaissance among African Americans in Indian Territory. Langston’s founding was made possible by the same federal land grant system that built other land-grant universities, though it was always underfunded and systemically disadvantaged compared to its white counterparts. Yet, its presence affirmed the centrality of education to the Black freedom struggle in Oklahoma.

However, the promise of self-determination was increasingly met with state-sanctioned repression. As Oklahoma moved toward statehood in 1907, white political leaders codified Jim Crow laws into the new state constitution. Despite its multicultural past, Oklahoma quickly aligned itself with the most repressive elements of Southern racial ideology. Segregation became law in schools, transportation, housing, and public accommodations. Black votes were suppressed through literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and poll taxes. Freedmen who had once held political office in tribal governance were now disenfranchised in the broader state system.

The early 20th century was marked by a crescendo of racial violence, culminating in the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. In the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Black Oklahomans had built one of the most prosperous Black communities in the United States. Often called “Black Wall Street,” Greenwood was home to doctors, lawyers, teachers, bankers, and entrepreneurs who had created a parallel economy that defied the logic of white supremacy. Their success, however, made them a target. On May 31 and June 1, 1921, a white mob—incited by racist media, tolerated by police, and aided by local officials—attacked Greenwood. Over 1,200 homes and businesses were destroyed, hundreds of people were killed or displaced, and no one was held accountable.

The massacre was not simply a spontaneous act of racial violence. It was the logical consequence of a society rooted in the legacies of slavery, where Black advancement was seen as a threat and white economic control was protected by force. The economic devastation wrought upon Greenwood’s Black residents was never repaired. Insurance claims were denied, lawsuits were dismissed, and survivors were forced to rebuild with little or no outside help. The loss of generational wealth from Greenwood represents one of the clearest examples of the economic afterlife of slavery—how systems born in human bondage continue to extract and destroy Black futures even long after slavery’s legal demise.

The rest of the 20th century brought new iterations of the slavery industrial complex to Oklahoma. The rise of the prison-industrial complex disproportionately incarcerated African Americans under the guise of law and order. Harsh sentencing laws, racial profiling, and the militarization of police forces resulted in a new form of bondage for many Black Oklahomans. Incarcerated people became part of a for-profit system that provided labor to private corporations, echoing the convict leasing systems of the post-Reconstruction South. Black communities also faced environmental racism, with oil and chemical industries placing polluting facilities in or near Black neighborhoods, leading to long-term health crises.

Educational inequities persisted. Despite the presence of Langston University, Black students across the state faced underfunded schools, segregated facilities, and tracking systems that diverted them away from college-bound paths. In higher education, universities such as the University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma State University often failed to confront their own racial histories or to adequately support Black students and faculty. These institutions benefited from the land theft and labor exploitation that defined Oklahoma’s post-slavery era, yet they rarely acknowledged their historical complicity.

Corporations based in or operating heavily within Oklahoma continue to profit from systems originally developed to exploit Black labor. Oil conglomerates like Devon Energy and Oneok trace their lineages back to companies that arose during the early 20th-century oil booms—booms made possible by land theft from Native and freedmen families. Agribusiness firms that dominate rural Oklahoma rely on low-wage, often precarious labor that echoes the plantation model. The state’s economic structure, dominated by extractive and exploitative industries, rests on a foundation laid during slavery and maintained through successive systems of racial capitalism.

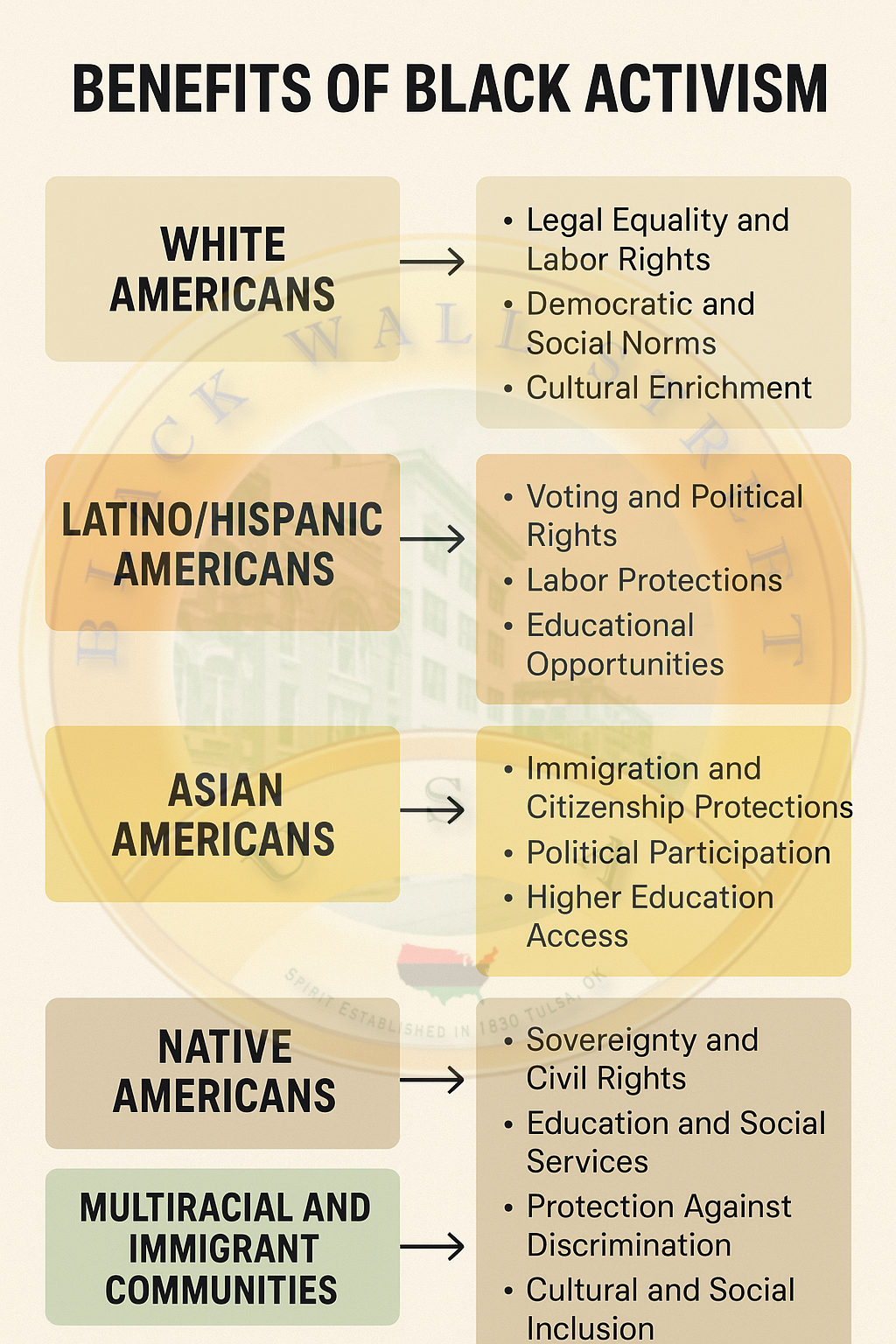

Nevertheless, the spirit of resistance has never been extinguished. Oklahoma has produced an enduring lineage of Black abolitionists, civil rights laborers, and freedom fighters who challenged the state’s foundational inequities. Clara Luper, a teacher and activist from Oklahoma City, led one of the first lunch counter sit-ins in the country in 1958—two years before the more widely known Greensboro sit-ins. Her students, known as the “Oklahoma City NAACP Youth Council,” faced physical violence, arrests, and harassment, but they persisted. Luper’s work laid the groundwork for desegregation in Oklahoma and helped galvanize the national civil rights movement.

Ralph Ellison, born in Oklahoma City, emerged as one of the most profound literary voices of the 20th century. In his novel Invisible Man, Ellison explored the psychic toll of racism and invisibility, themes born from his lived experience in a state that simultaneously erased and exploited Black identity. His work reflects the intellectual and artistic legacy of Oklahoma’s African-descended peoples, forged in the crucible of post-emancipation struggle.

More recently, activists and scholars have reignited the demand for reparations for the survivors and descendants of the Tulsa Race Massacre. Legal challenges have sought to force the city and state to address the economic and human toll of the massacre. These efforts are not merely about restitution; they represent a broader movement to reckon with the enduring legacy of slavery in Oklahoma—a legacy encoded in law, culture, and economy.

The story of slavery in Oklahoma is neither marginal nor exceptional. It is central to understanding how racial domination evolved in the American interior and how the nation’s economic and ideological foundations were built on the labor, suffering, and ingenuity of enslaved peoples. From the forced marches of the Trail of Tears to the burning of Greenwood, from the Black towns of Indian Territory to the prison cells of the modern carceral state, the continuum of slavery has never been broken—only transformed.

The mid-20th century was marked by the expanding reach of federal programs and wartime industrialization, which offered new employment opportunities for many Americans but rarely improved the plight of Black Oklahomans. World War II brought temporary jobs in munitions plants, railroads, and military installations like Tinker Air Force Base. However, African Americans were often relegated to the lowest-paying, most dangerous tasks, with few avenues for long-term economic mobility. Many Black men were drafted into segregated units of the military, where they endured racial discrimination in both barracks and battlefields.

Upon returning to Oklahoma, they encountered the same racially segregated society they had left behind, despite having risked their lives for democratic ideals abroad. The G.I. Bill, which helped transform the white middle class after the war, was administered in such a way in Oklahoma that Black veterans were often denied home loans, college access, and employment support. The systemic denial of these benefits perpetuated the racial wealth gap initiated by slavery and deepened during Reconstruction.

The persistence of racially restrictive covenants in cities like Tulsa, Oklahoma City, and Lawton ensured that Black families remained confined to underdeveloped and underserved neighborhoods. These racially coded property restrictions operated alongside redlining maps created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, which labeled Black neighborhoods as “hazardous” and denied their residents access to federally insured loans. This practice made it nearly impossible for Black families to accumulate equity or transfer intergenerational wealth, a mechanism of economic oppression deeply tied to the legacy of slavery. Public housing projects, constructed during this same period, were overwhelmingly located in Black neighborhoods and often reinforced spatial segregation, environmental exposure, and surveillance.

Meanwhile, Oklahoma's Black children were confined to underfunded, overcrowded schools. Even after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision declared segregation unconstitutional, Oklahoma officials found ways to delay or resist integration. Dual school systems persisted in all but name, and Black teachers were frequently dismissed under the guise of consolidation. The Oklahoma State Department of Education, in collusion with white school boards, often reallocated resources away from historically Black schools even as they were being desegregated. This systemic educational deprivation curtailed opportunities for African American youth and restricted their entry into higher education, professional careers, and civic leadership. These educational disparities were a direct continuation of the enslaver's intention to control the intellectual development of Black people, dating back to prohibitions on literacy among the enslaved in Indian Territory and the broader South.

During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, Oklahoma became both a site of resistance and a battleground for racial justice. Building upon the foundations laid by Clara Luper and the NAACP Youth Council, activists across the state waged campaigns for school desegregation, fair employment, open housing, and voter rights. While Oklahoma was not the national flashpoint that states like Alabama or Mississippi became, it was no less hostile to civil rights efforts. Local governments, police departments, and white citizens' councils coordinated to suppress protests, harass organizers, and block the enforcement of civil rights legislation.

The Oklahoma legislature, influenced by the white electorate and corporate donors, passed laws designed to weaken civil rights enforcement, obstruct affirmative action, and criminalize dissent. Black students who integrated white schools faced constant intimidation, and Black families who moved into white neighborhoods were often the targets of arson, vandalism, and threats. The very act of demanding full citizenship rights exposed Black Oklahomans to a system of legal, social, and economic punishment. These responses mirrored antebellum systems of control, wherein attempts by enslaved people to escape, educate themselves, or organize rebellions were met with swift and brutal reprisals.

Economic exclusion remained a defining feature of Black life in Oklahoma through the latter half of the 20th century. The state’s largest industries—oil, gas, cattle, and agriculture—continued to profit from Black labor while systematically excluding Black workers from positions of authority, ownership, or substantial compensation. Oil giants such as Kerr-McGee, founded in Oklahoma City, and multinational energy conglomerates like Devon Energy maintained racially exclusionary hiring practices well into the 1980s. The exploitation of natural resources was accompanied by the marginalization of the Black communities closest to the extraction sites, who bore the brunt of pollution, land degradation, and displacement.

Railroad companies like the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway employed thousands of Black men as porters and maintenance workers but denied them career advancement, union representation, and workplace protections. These jobs, which were often held by the descendants of freedmen, became emblematic of the economic ceiling imposed by racial capitalism. Black women, meanwhile, were largely confined to domestic work or low-paid positions in segregated nursing homes, schools, and hospitals. The cumulative result of these patterns was the entrenchment of a racialized labor hierarchy that mirrored the plantation model of slavery: white ownership at the top, Black labor at the bottom, and a legal and cultural system that ensured the perpetuation of the imbalance.

As suburbanization swept across Oklahoma in the postwar decades, fueled by federal highway construction and homeownership subsidies, Black communities were often left behind or displaced. Urban renewal projects in cities like Tulsa and Oklahoma City targeted Black neighborhoods for demolition, rebranding them as “blighted” while ignoring decades of disinvestment.

In the 1960s and 1970s, entire Black districts were razed to make way for highways, shopping centers, and government buildings. The Greenwood District, already decimated by the 1921 massacre, was subjected to further disintegration through urban planning decisions that fractured its social fabric and destroyed economic infrastructure. This systematic erasure mirrored earlier patterns of displacement during the Trail of Tears and Reconstruction, where the gains made by Black and Indigenous people were undermined by state-sanctioned removal and redevelopment.

By the 1980s, mass incarceration emerged as the dominant mechanism for controlling Black populations in Oklahoma. Fueled by the War on Drugs, the expansion of private prisons, and the rise of punitive sentencing laws, the state developed one of the highest incarceration rates in the nation—particularly for Black men. Facilities like the Lawton Correctional Facility and the Davis Correctional Facility became emblematic of a new economy rooted in carceral labor. Inmates were leased out to private corporations to work for pennies per hour, manufacturing furniture, textiles, and other goods in what amounted to a modern-day extension of convict leasing. The for-profit prison system recreated the conditions of enslavement under a different name, criminalizing poverty, addiction, and protest while extracting labor from a disproportionately Black inmate population.

The school-to-prison pipeline also took root in Oklahoma during this period, with Black children more likely to face suspension, expulsion, and arrest in schools than their white peers. Zero-tolerance policies, school police, and discriminatory discipline reinforced the criminalization of Black youth and diminished their access to quality education. These mechanisms of control were not anomalies but continuations of an old design—the systematic denial of mobility, literacy, and freedom that undergirded chattel slavery in Indian Territory and beyond. Even into the 21st century, the educational, judicial, and economic systems of Oklahoma continue to function as engines of racial subjugation and wealth extraction.

The persistence of these disparities has prompted new generations of scholars, activists, and descendants to interrogate the unfinished business of abolition in Oklahoma. In recent years, lawsuits filed by descendants of Tulsa Massacre victims have sought reparations for lost wealth, land, and lives. These lawsuits are not simply about economic compensation; they are attempts to rectify a continuum of harm that began with enslavement and has extended through every generation. Simultaneously, descendants of freedmen have renewed their legal battles for full tribal citizenship, demanding the implementation of treaty rights signed in 1866. These struggles reveal how the afterlife of slavery remains encoded in the legal and institutional DNA of the state.

Colleges and universities in Oklahoma have also come under increased scrutiny. While Langston University has continued to serve as a bastion of Black higher education, other major institutions—such as the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma State University, and Tulsa University—have begun to face calls for transparency and reckoning. These schools were founded on land acquired through the displacement of Indigenous people and, in many cases, benefited from freedmen labor or the segregationist policies of the Jim Crow era. Their donor bases, endowments, and infrastructure frequently carry the imprints of corporations that profited from slavery, peonage, or apartheid labor practices. Yet few have established formal processes to acknowledge or redress these legacies.

Corporations headquartered in Oklahoma, including energy giants, agricultural conglomerates, and logistics firms, continue to profit from the racialized geography of the state. Black neighborhoods remain disproportionately exposed to pollution, underemployment, and lack of access to healthcare. Data consistently shows higher infant mortality rates, shorter life expectancy, and increased chronic illness in these communities. Meanwhile, the political apparatus of Oklahoma has remained largely unresponsive to calls for reparative justice. State leaders have often resisted civil rights measures, opposed racial equity programs, and promoted laws aimed at criminalizing protest and curbing educational curricula that discuss systemic racism or the history of slavery.

Despite these formidable barriers, Black Oklahomans have continued to resist, build, and reimagine their futures. The resurgence of the Greenwood District as a cultural and entrepreneurial center represents both a symbolic and material effort to reclaim lost heritage. Organizations like the Greenwood Cultural Center, the Oklahoma African American Educators Hall of Fame, and local branches of the NAACP and Urban League have amplified the voices of those demanding justice. Independent Black media, churches, and educational institutions remain vital platforms for historical memory and civic engagement.

Recent national movements such as Black Lives Matter have found resonance in Oklahoma, where the names of Terence Crutcher and Isaiah Lewis have become rallying cries for police accountability. Young activists have taken up the mantle of Clara Luper, organizing protests, educational forums, and policy campaigns to address the deep roots of racial injustice. They draw upon a long tradition of Black radicalism in the state—one forged in the crucible of slavery, refined through the fires of massacre, and sustained through generations of struggle.

In this way, Oklahoma’s legacy of slavery is not confined to archives or ruins; it lives on in the bodies, memories, and movements of its people. It is inscribed in court records, land deeds, school textbooks, and corporate ledgers. It echoes in the songs of freedmen choirs, the sermons of liberation theologians, and the poetry of descendants who refuse to forget. It demands not only historical acknowledgment but also reparative action—an end to the systems that continue to commodify, punish, and silence Black life.

To understand slavery in Oklahoma is to understand a multigenerational war over labor, land, and belonging. It is to see how the plantation was reimagined as the prison, the classroom as a battleground, and the ballot box as a site of exclusion. It is to recognize that the moral injury of slavery has never healed, because the structures built upon it have never been dismantled. And it is to realize that, amid all this, a people have endured—not as victims, but as visionaries of freedom not yet fully realized.

To complete the story of slavery in Oklahoma is not to draw a clean conclusion but to reckon with the weight of a history that is both unfinished and ongoing. Slavery, as it was practiced within the bounds of Indian Territory and the eventual state of Oklahoma, did not end in a single act of emancipation, nor did its ideologies die with the Civil War. Instead, slavery morphed—structurally, ideologically, and economically—into systems that continued to confine, exploit, and criminalize African-descended people in Oklahoma. From Indian bondage to oilfield exploitation, from the plantation to the prison, from redlining to school closures, every generation has inherited and resisted a system born in the trafficking of human beings.

The long shadow of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the Trail of Tears continues to loom over Oklahoma’s historical landscape. These acts of racialized expropriation not only displaced Native nations but also set the stage for the integration of African chattel slavery into Indian governance. The Five Tribes, by adopting the slave system as a form of cultural and political survival, unintentionally constructed a foundational paradox: the simultaneous assertion of Indigenous sovereignty and the perpetuation of Black enslavement. This paradox was not resolved with the Civil War, nor with the treaties of 1866, because the structures of economic dependence and racial caste remained embedded in the emerging institutions of the territory and, later, the state.

This foundational contradiction was never fully addressed by the U.S. government, which consistently prioritized settler expansion over equitable justice. The federal government’s failure to enforce the citizenship and land rights of freedmen, despite treaty obligations, amounted to a second dispossession—a betrayal of the promise of emancipation. By the time Oklahoma achieved statehood in 1907, the political and economic terrain had already been restructured to ensure that freedmen and their descendants remained subordinate. The racial caste system that governed the cotton fields of Mississippi and the sugar plantations of Louisiana was reproduced in the pecan orchards, cattle ranches, and oil fields of Oklahoma.

Even the geography of Oklahoma reflects this history. The land once allotted to freedmen under the Dawes Act has, in many cases, been absorbed into white ownership through fraud, violence, or eminent domain. The remaining freedmen communities, often located in rural isolation or urban peripheries, suffer from disinvestment and neglect. Basic infrastructure—clean water, sewage systems, internet access, road maintenance—is often absent or inadequate in these areas. Meanwhile, extractive industries that grew rich on the land and labor of Black and Indigenous people have paid little back into the communities they helped disfigure. Environmental degradation, from fracking to waste dumping, disproportionately affects Black and freedmen populations, further entrenching cycles of illness, poverty, and displacement.

Modern state policy in Oklahoma frequently mirrors the paternalistic logic of the enslaver. Welfare programs are stigmatized and underfunded, yet policing budgets are bloated and militarized. Black children are disproportionately targeted for school discipline, referred to law enforcement, and funneled into juvenile detention centers.

The Oklahoma Department of Corrections operates as a massive and racially skewed apparatus of incarceration, where Black men comprise a significantly disproportionate share of the prison population. Private prison companies, such as CoreCivic and GEO Group, have found a fertile operating ground in Oklahoma, where legislation has favored punitive sentencing and mandatory minimums. These companies profit from the warehousing of Black bodies, often for non-violent offenses, replicating the economic exploitation of slavery under a legal guise.

Even cultural memory is contested terrain. For decades, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre was excluded from Oklahoma school curricula. Survivors were ignored, their stories silenced, their demands for justice dismissed. Only in the past two decades have serious efforts been made to recover and publicize this history, largely due to grassroots pressure and scholarly research. Yet even now, debates over how to teach slavery, racism, and systemic injustice have reignited, with state legislatures introducing bills to restrict “divisive” topics in classrooms. These attempts to sanitize history perpetuate the intellectual subjugation that once forbade the enslaved from reading or writing.

The struggle for tribal citizenship among freedmen descendants continues into the 21st century. While the Cherokee Nation, after legal challenges and community pressure, restored full citizenship rights to its freedmen in 2017, other tribes such as the Chickasaw and Choctaw have continued to resist or limit inclusion. These ongoing disputes are not merely administrative; they reflect unresolved questions about race, belonging, and the legacy of slavery within Native nations. They also challenge the U.S. government’s continued abdication of its responsibilities, particularly in upholding the 1866 treaties and ensuring that citizenship is not weaponized as a tool of exclusion.

The economic inequality birthed by slavery and nurtured by its successor systems remains staggering. Black households in Oklahoma continue to earn significantly less than their white counterparts. Homeownership, one of the primary vehicles for intergenerational wealth, remains disproportionately out of reach for Black families, not simply due to income disparities but because of decades of discriminatory lending, appraisals, zoning laws, and outright theft. The value of land once held by freedmen—both its literal and symbolic worth—has been appropriated by municipalities, universities, and private developers without compensation. Oklahoma’s major banks, insurance companies, and utility providers have also played roles in reinforcing inequality, sometimes by denying services or charging higher rates to predominantly Black neighborhoods.

Education remains a central site of contestation and potential transformation. Despite persistent underfunding, Black educators, parents, and students have fought to sustain excellence and equity in public schools. The resurgence of interest in Oklahoma’s Black history has inspired new curricula, oral history projects, and commemorative initiatives, many of them community-driven. Langston University continues to serve as a cultural and academic anchor for the state’s African American population, producing generations of scholars, artists, clergy, and public servants committed to justice. Yet even Langston faces structural challenges, from state funding disparities to declining enrollment amid broader efforts to defund public higher education.

In the spiritual domain, Black churches in Oklahoma have long served as pillars of resistance and renewal. From rural sanctuaries in freedmen towns to urban congregations in Tulsa and Oklahoma City, these churches have provided not only religious guidance but also social services, civic education, and political mobilization. Clergy such as Reverend Ben H. Hill and Reverend W.K. Jackson led voter registration drives, protested racial violence, and organized economic cooperatives. Their ministries, rooted in the theology of liberation, have often spoken directly to the legacy of slavery, invoking biblical and African traditions to affirm the dignity of Black life.

The call for reparations in Oklahoma, while long-standing, has gained renewed urgency and coherence in the contemporary era. Advocates have advanced a range of proposals: direct compensation to descendants of Tulsa massacre victims; restoration of tribal citizenship to all freedmen; land return programs; targeted investment in Black schools, businesses, and neighborhoods; and the creation of truth and reconciliation commissions to investigate historical injustices. These demands are not mere symbolic gestures; they represent a moral and economic reckoning with the structures of slavery that built the state and continue to govern its operations.

Reparative justice also includes institutional accountability. Universities must not only acknowledge their historical ties to slavery and segregation but take concrete steps to rectify those harms—through endowed scholarships for descendants of the enslaved, inclusion of Black studies in core curricula, and the diversification of leadership. Corporations with roots in extractive economies must fund environmental restoration and community reinvestment in the neighborhoods they helped impoverish. The state government must repeal laws that criminalize poverty, protest, and the teaching of history, and must adopt comprehensive reforms in housing, employment, and health that specifically address racial disparities born of slavery.

Importantly, the fight for justice in Oklahoma is not the work of a single group or generation. It is an intergenerational movement forged by survivors, teachers, elders, and youth who refuse to allow silence to become policy. It includes the families still grieving from mass incarceration, the educators writing curricula in defiance of legislative bans, the historians excavating erased records, and the artists rendering visible what was meant to be forgotten. It includes the descendants of those who walked the Trail of Tears and those who toiled in bondage beside them. It includes the children of Greenwood, whose ancestors built wealth from nothing, only to see it burned, and who now return to reclaim their legacy with brilliance, defiance, and clarity.

The story of slavery in Oklahoma, then, is not only a tale of brutality but also one of vision. Enslaved people envisioned freedom even in chains. Freedmen built towns where none thought they could thrive. Survivors of massacre dreamed of restoration even among ashes. This vision persists. It calls to us from courtrooms and classrooms, from street corners and sanctuaries, from family archives and public monuments. It demands that we reckon with what was done, what was denied, and what still must be made right.

To write the history of slavery in Oklahoma is to indict a nation and summon its conscience. It is to say: here, too, were plantations. Here, too, were whips and auctions, profit and pain. Here, too, were resistors and rebuilders, teachers and truth-tellers. Here, too, the legacy lives—not in chains, but in contracts; not in plantations, but in prisons; not in overseers, but in algorithms; not in cotton fields, but in corporate boardrooms. And yet, here too, lives the possibility of freedom—not as myth or metaphor, but as policy, as justice, as change.

This is the full arc of Oklahoma’s slavery story—not a chapter to be closed, but a foundation upon which to build a better future. That future will not come through erasure or silence but through radical honesty, systemic transformation, and the redistribution of power and wealth long stolen. In the words of poet Audre Lorde, “It is not difference which immobilizes us, but silence.” And in Oklahoma, the time for silence has ended.

History, when told truthfully, does not merely reflect the past—it refracts it through the lens of justice. And justice, in this land shaped by stolen bodies and broken treaties, must begin with remembrance, restitution, and resolve. Only then can the story of slavery in Oklahoma be complete. Only then can it begin to heal.

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

BlackWallStreet.org

Slave Records By State

See: Slave Records By State

Freedmen's Bureau Records

See: Freedmen's Bureau Online

American Slavery Records

See: American Slavery Records

American Slavery: Slave Narratives

See: Slave Narratives

American Slavery: Slave Owners

See: Slave Owners

American Slavery: Slave Records By County

See: Slave Records By County

American Slavery: Underground Railroad

See: American Slavery: Underground Railroad